This is the final installment of the Building a Healthcare System from Scratch series, and it begins with the same caveat as Part 7—to understand the rationale behind the ideas presented, you need to read and understand all the prior parts of the series, beginning at Part 1.

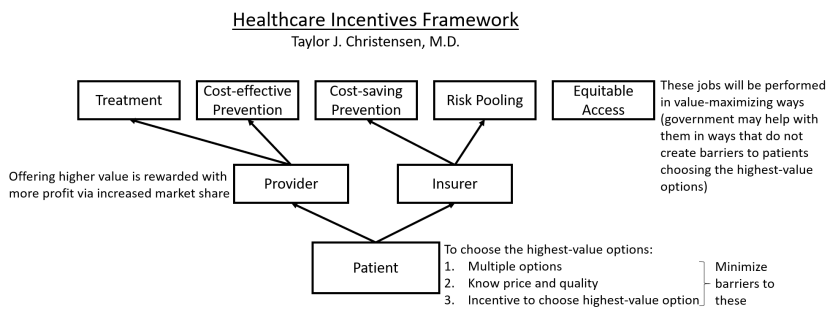

Now that I have explained the Healthcare Incentives Framework (Parts 1 through 6) and described what various types of systems would look like that have implemented the principles of it (Part 7), we are ready to look at something more complex: rather than building an optimal system from scratch, how can this framework be applied to an existing system that needs fixing? The American healthcare system will be a perfect case study for this.

Where it sits right now, the American healthcare system seems to land somewhere in between the libertarian-type system and the single-payer system described in Part 7, except that it fails to implement the majority of the principles of the framework. It is also overly complex, which contributes greatly to its impressive administrative expenses. So what could a much-simplified American healthcare system look like that also maximally implements the principles of this framework? With consideration for and much guessing about Americans’ preferences regarding healthcare, here is an imagined description . . .

The United States eventually chose to strengthen its individual mandate. The government now mandates all people, without exception, to have a healthcare insurance plan that covers all services included on its list of “essential health benefits.” For those who forego insurance coverage, they pay a tax penalty that ends up being nearly the same as the premiums they would have paid. If uninsured individuals receive care that they cannot afford, they usually end up having to either go on long-term repayment plans or declare bankruptcy because there is no bailout available for them.

The website healthcare.gov has become the ultimate source for healthcare insurance shopping. All qualified insurance plans (i.e., plans that cover all the essential health benefits) are listed there, along with their coverage level (according to the metal tiers), prices, and a short description that highlights any other benefits the plan offers that may help prevent healthcare expenditures.

Premium subsidies are available to all whose premiums will exceed a certain percentage of their income, and the subsidy amount is pegged to the second-cheapest qualified insurance plan available to them. The subsidies are automatically applied at the time people are choosing a plan on healthcare.gov. Because this system worked so well and was basically duplicative of Medicare and Medicaid, both programs were slowly phased out, which decreased insurance churn and increased time horizons. However, a vestige of Medicaid remains in that, depending on an individual’s annual income, there are also limits on how much they can be required to pay out of pocket for care.

The government also did away with the employer mandate and somehow found the political willpower to repeal all tax breaks for healthcare expenditures, which eventually led to employers getting out of the business of providing healthcare insurance for their employees and just giving that money to employees directly as regular pay.

Altogether, these changes mean that all Americans shop for their healthcare insurance on healthcare.gov. For anyone who is unable to do this themselves, there is a phone number to call to connect with someone who can assist them in selecting the plan that seems best for them.

A few changes were also made to encourage more insurance options. First, many regulations were eliminated, including the medical loss ratio requirement and state insurance department approvals of rates. These became unnecessary after people began to be able to compare the value of different insurance plans and choose based on that because overpriced or low-value plans (either from too much overhead or too high of rates in general) lost market share and profit. State-specific insurance regulations were standardized so that insurers can easily expand to new markets. And a law was passed requiring transparency of all price agreements between providers and insurers, which made the process of forming contracts with providers in a new region easier. These policies led to almost all markets having multiple options for each coverage tier.

In this way, the United States achieved universal access to affordable healthcare insurance relying on the private market while preserving the ability and incentive for all people to select the highest-value insurance plan for them. As a result, insurance plans aggressively innovate to find ways to prevent care episodes so that they can offer lower premiums and attract higher market share. Insurers also found that implementing differential cost-sharing requirements led people to start choosing lower-priced providers, which also enabled the insurer to lower premiums further. Finding provider prices has become easier ever since the price transparency law was passed.

The government has had to help overcome the problems caused by a multi-payer system by enforcing some standardization, including uniform insurance forms/processes, standardized bundles of care that all insurers in a region either agree or disagree to implement together, and standardized quality metrics that providers are required to report. These quality metrics are not used for bonuses, so they have been changed to be more focused on what patients need to know to choose between providers for specific services.

These quality metrics are now reported on an additional section on healthcare.gov that lists all providers, their quality metrics, and their prices (seen as your expected out-of-pocket cost if you log in) in an easy-to-compare format. Due to patients’ differential cost sharing requirements for most services, as well as broad common knowledge of the existence and utility of this website, most patients have begun to refer to it before choosing providers. This part of healthcare.gov has even been developed into a highly rated smartphone app.

In response to these changes, providers found that their value relative to competitors largely determined their market share and profitability, which unleashed an unsurpassed degree of value-improving innovation. The cost of care in the United States was previously so high that the majority of those initial innovations led to much cheaper care, which led to much lower insurance premiums and eased the premium subsidy burden on the federal government. Thanks to these changes, the federal deficit has begun to sustainably diminish quicker than any budgetary forecasting model could have predicted, which has also helped stabilize the American economy.

There are still barriers to people being able to identify and choose the highest-value insurers and providers. There are many important aspects of quality that are unmeasurable. Many people do not have the health literacy required to figure out which insurance plan or provider would be best for their situation and preferences, despite the ease of comparison enabled by healthcare.gov. There are medical emergencies that do not allow shopping (although the number of these has turned out to be much less than was previously thought because most of what used to present to emergency departments were not actually emergencies).

In spite of these lingering barriers, enough patients are choosing the higher-value options that providers and insurers still have a strong incentive to innovate to improve their value so they can win the market share and profit rewards available to higher-value competitors. And the result is that Americans are being kept healthy more often and are receiving care that is higher quality and more affordable.

That concludes my imagined description of how the American healthcare system could look with the principles from the Healthcare Incentives Framework fully applied. Just as a reminder, it represents merely a guess of how it could end up given the current system. This is by no means the only way to apply the principles of this framework, nor is it my secret idealized version of how it could end up. But I hope it was useful and thought provoking as a case study!

We have come a long way in this series. Throughout it, I worked hard to make the principles of the Healthcare Incentives Framework clear, and I hope the concrete examples have helped solidify those as well as demonstrate their potential for sustainably fixing healthcare systems around the world. If you want a more academic treatment on this framework (at least the part of it that applies specifically to providers), I published that as a medical student.

I intend to help policy makers of all types find ways to apply the principles discussed in this series. Please contact me if you have questions or would like me to help work through potential applications. Contact info is on my About Me and This Blog page. In the meantime, I hope you will follow along as I continue to blog about how to fix our healthcare system!