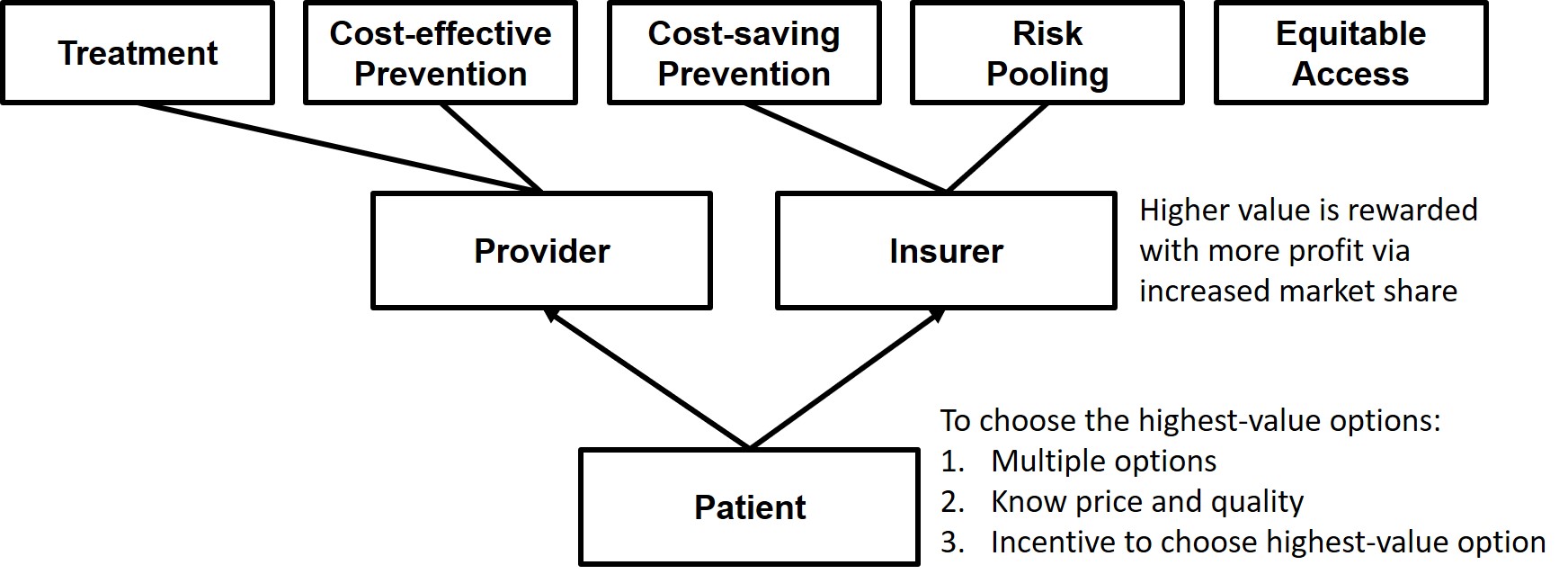

Last week, I wrote about how quality metrics are misused by healthcare reformers. They’re almost exclusively tied to bonuses or penalties from insurers. In other words, they’re used to increase or decrease the price providers get paid. This is a form of administrative pricing, which is a super economically inefficient way to set prices. And I proposed the alternative use of quality metrics–to help patients choose higher-value providers.

We give people quality metrics and they seem to generally do a good job shopping for the best value in pretty much every other industry, which drives competition over value. So why do we fail so miserably in healthcare?

The first problem is that healthcare is missing the thing that motives people to shop around for the best value: their money is on the line. I wrote about this a couple weeks ago. We need people to pay a little more if they choose a higher-priced provider. But when prices are opaque or unknowable beforehand, or when their insurance plan makes them pay the same regardless of the provider’s price (or if the insurance plan is complex enough that the patient doesn’t understand that they’ll have to pay more if they choose a higher-priced provider), people don’t perceive that their money is on the line. In that last sentence, I just listed four issues preventing people from actually caring what the price is!

And then there are the issues of having only one option (like in a rural area) and non-shoppable services (like during emergencies) and non-shopping-when-you’re-already-established-with-a-provider. Yeah, there are a lot of reasons people don’t shop for prices in healthcare! But in spite of all that, there are some good studies that show that people will actually shop for services when all the stars align.

I know that even if people have a hard time knowing prices beforehand, they theoretically could still shop just as vigorously for the highest quality.

But I think there’s something that happens when people can’t shop for price that sorta stops them from thinking about shopping for quality too. I haven’t seen any studies that prove this, but I suspect it’s a thing.

So let’s talk about the people who say, “Well if I don’t know what I’m going to pay, I might as well try to find the best quality option.” They use a variety of sources since there isn’t one single well-known and useful quality source out there. Usually they rely on recommendations from their doctor or their friends and family. If that person had a good experience, that’s a reliable indicator of quality, right?

Or maybe they decide to be brave and try Googling quality metrics. They’ll find something, certainly. But chances are they’ll find quality metrics that aren’t super relevant to what they actually care about. For example, maybe they’ll discover Medicare’s Care Compare website. What does 3 stars even mean? Even drilling down, how useful is it to know that a hospital’s safety is “below the national average” in 2 out of 8 metrics? How does that get weighed against a high recommendation of the hospital from a family member? Or, is that quality rating ignored because the hospital’s lobby is spacious and it advertises meals prepared by well-known chefs?

Compare the relative uselessness of those quality metrics to the example of Seattle’s Virginia Mason Health System when they were redesigning their low-back pain care pathway. They figured out that people care most about how soon they can get back to work (it’s expensive to live in Seattle, if you didn’t know) and, among other changes, made same-day appointments available. This was the quality metric people cared about, and their low-back-pain market share doubled.

After reading all these barriers to people shopping for the best value in healthcare, I hope you can see that (1) this problem is perfectly explainable and (2) it’s totally fixable. Can someone please tell the Medicare administrators that most of their current efforts at “value-based purchasing” are going to be close to useless? And tell them to look at getting rid of some of these barriers to patients choosing high-value providers instead.