I usually write about how to fix healthcare (and also, lately, monetary policy). But I also cover other government-related topics. And since President Trump has been pushing tariffs so strongly lately (even going so far as to establish an External Revenue Service, ostensibly to make other countries fund our government rather than making Americans fund it through internal taxation), I spent some time refreshing my understanding of the economics of tariffs. This post is a consolidation of what I’ve learned.

Disclaimer: This is not meant to be a political post, but of course any time I discuss highly politicized policies, it will have strong political implications. So, to be clear up front, I will state that my goal with this post is the same as it always is on this blog: I want to provide an easily comprehensible explanation of the principles that underly a topic. Doing so forces me to think through and understand them better, and I hope it also helps others to understand more about the topic. Then we can all take that information, merge it with our other knowledge, and then look at it through the lens of our personal moral philosophy to decide what we think about specific policies. And for anyone curious about my biases, see here.

Now, let’s talk about tariffs. The source for most of this information is the textbook Economics, by Samuelson and Nordhaus.

First, a definition: A tariff is a tax imposed by the government on goods or services imported from other countries.

Note that services can be “imported” too even though they’re not physically being brought to the country. An example of a service that is commonly imported to the U.S. is tech support. Tariffs work the same for services as they do for goods, so, for the sake of brevity, I’ll refer exclusively to goods for the rest of this article.

There is a spectrum for how narrowly or broadly a tariff can apply. For example, it could be narrow enough to only apply to a single good from a single foreign country. Or it could apply to a single good from all foreign countries. Or it could apply to all goods from a single foreign country. There are lots of options–the choice of how broad or narrow to make the tariff all depends on what the policy makers are hoping to achieve with it.

And there’s one last point I want to make before I get into the details: When economists are drawing their supply and demand graphs, they use quantity on the X axis and price on the Y axis. I understand why price is used–it’s an easily quantifiable number. But this is an oversimplification. The demand for an item isn’t solely based on price; it’s based on both price and quality (i.e., value). The value of a good is what shapes how much money consumers are willing to put toward that good verses other goods. For example, if a good stays the same price but its quality improves substantially, people will be willing to dedicate a larger share of their wealth to obtaining that good. So, over the course of this post, when I’m comparing the domestic price of a good to the world price of that good, really what I should be doing is comparing the domestic value of that good compared to the world value of it. But, calculating the value of something is difficult if not impossible since it relies on subjective interpretations of what quality means to each consumer, so I’ll just stick with price. Fortunately, the conclusions of this analysis are the same either way.

Ok, now let’s get into the nuts and bolts of tariffs, and then we can analyze some different applications of them after that. For this example, let’s use clothing and simple numbers.

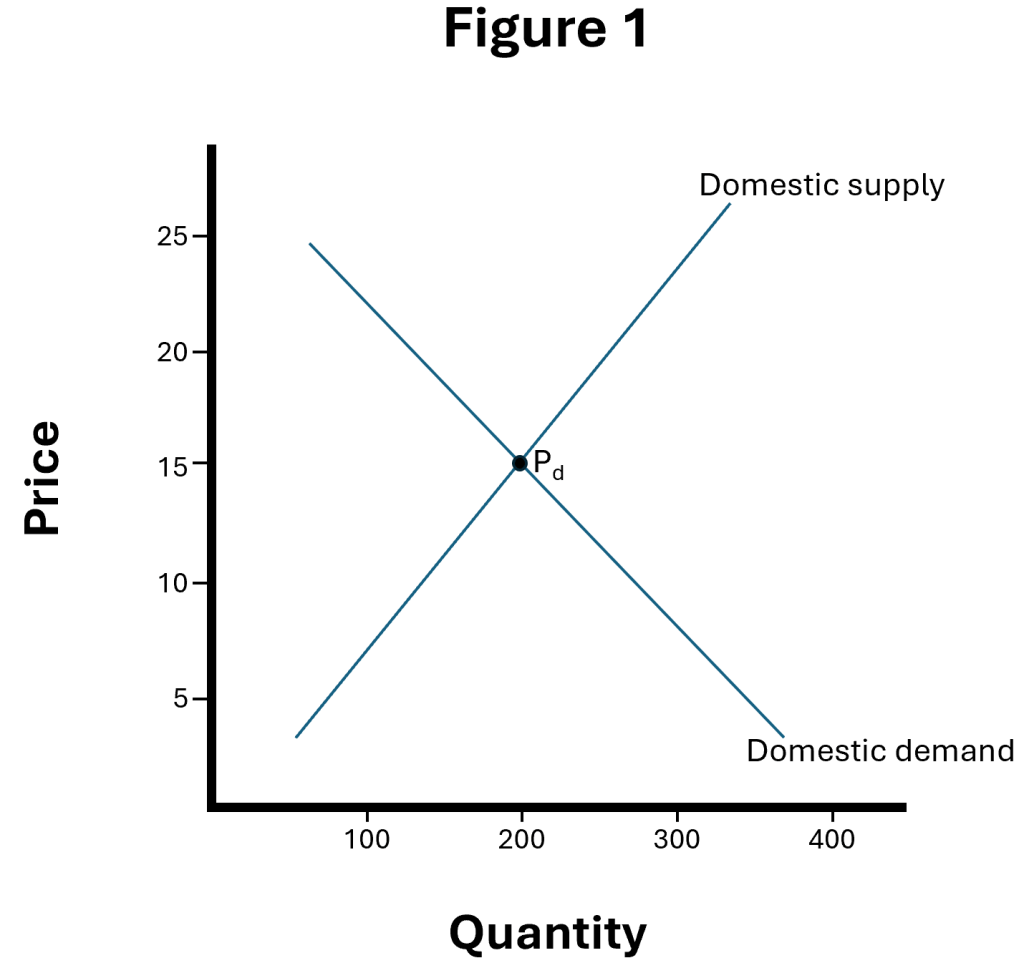

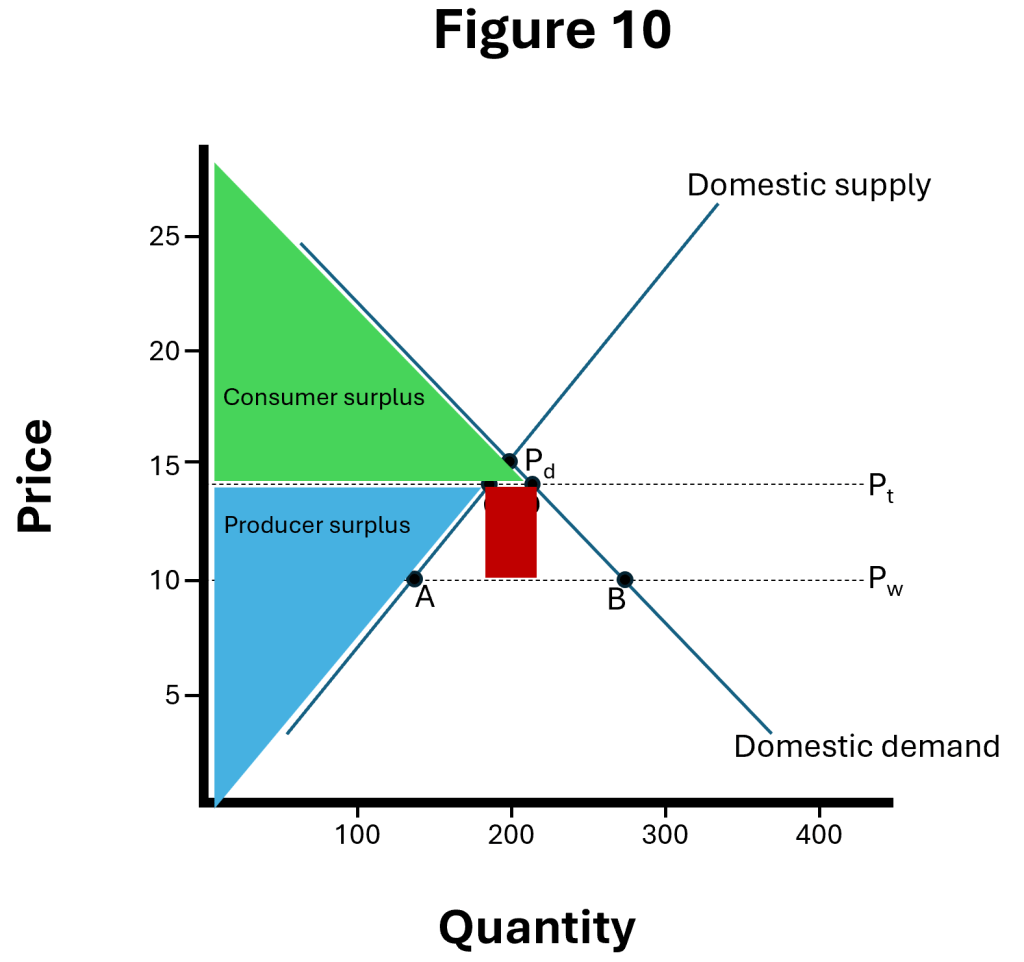

First, let’s pretend international trade doesn’t exist. This is how the domestic clothing market looks:

The price of clothing would be Pd, which stands for the domestic equilibrium price, which is $15. And, at that price, the quantity demanded would be 200 units.

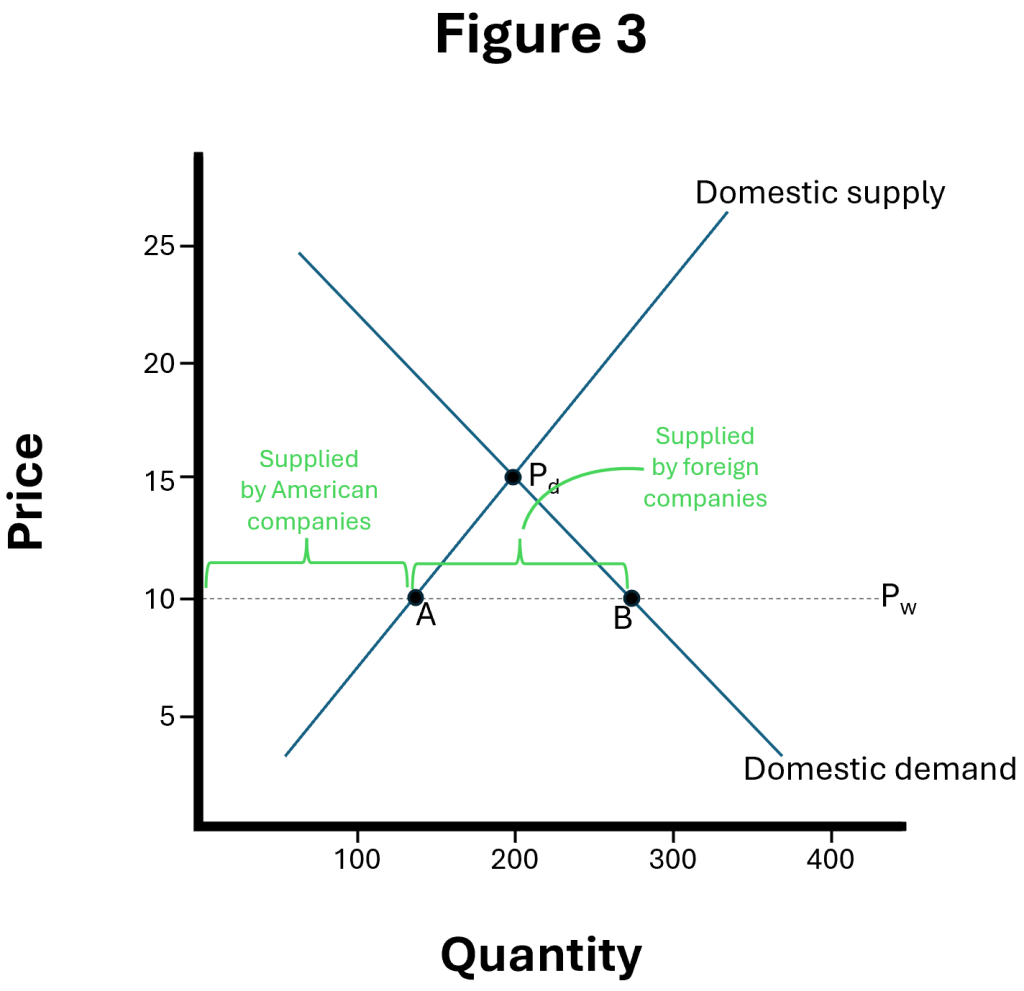

Now let’s add in worldwide free trade with no tariffs. If the world price (Pw) is only $10 (including transportation costs), this is how it would look:

That horizontal dashed line I added is the world price, which is $10. The price is so much lower than the domestic price that the quantity demanded is all the way up to about 275 units now (see point B on the figure), and that is supplied by a mix of domestic producers and foreign producers. Let’s look specifically at the X axis to see how much comes from each one.

We can see how much comes from domestic producers by looking at how much they’re willing to supply at that price of $10 (point A on the figure), which looks to be at around 125 units (rounding for simplicity). And the difference is made up by foreign producers (the distance from point A to point B), which is about 150 units (275 – 125).

Therefore, with free trade and no tariffs, American consumers would be saving $5 per unit of clothing they buy, and, of the total 275 units that they would be buying, 125 would be produced domestically and the other 150 would be imported, as demonstrated in Figure 3:

The important thing with this change is looking at (1) how much free trade benefited domestic consumers and (2) how much free trade hurt domestic producers.

We can calculate that by comparing the change in consumer surplus and producer surplus from Figure 1 to Figure 2.

Consumer surplus looks at how much each person who bought the good was willing to pay compared to how much they actually had to pay, and it adds all of those individual surpluses together.

Producer surplus is similar–it looks at the lowest price each company was willing to sell its goods for compared to how much it actually sold its goods for, and it adds all of those surpluses together.

Surpluses are what we want–it means the consumer or producer gets to retain more wealth than they would have been able to otherwise, which gives them room to do other useful things with that wealth.

Here’s the consumer surplus and producer surplus for the zero-international-trade situation:

And here they are for the free trade situation:

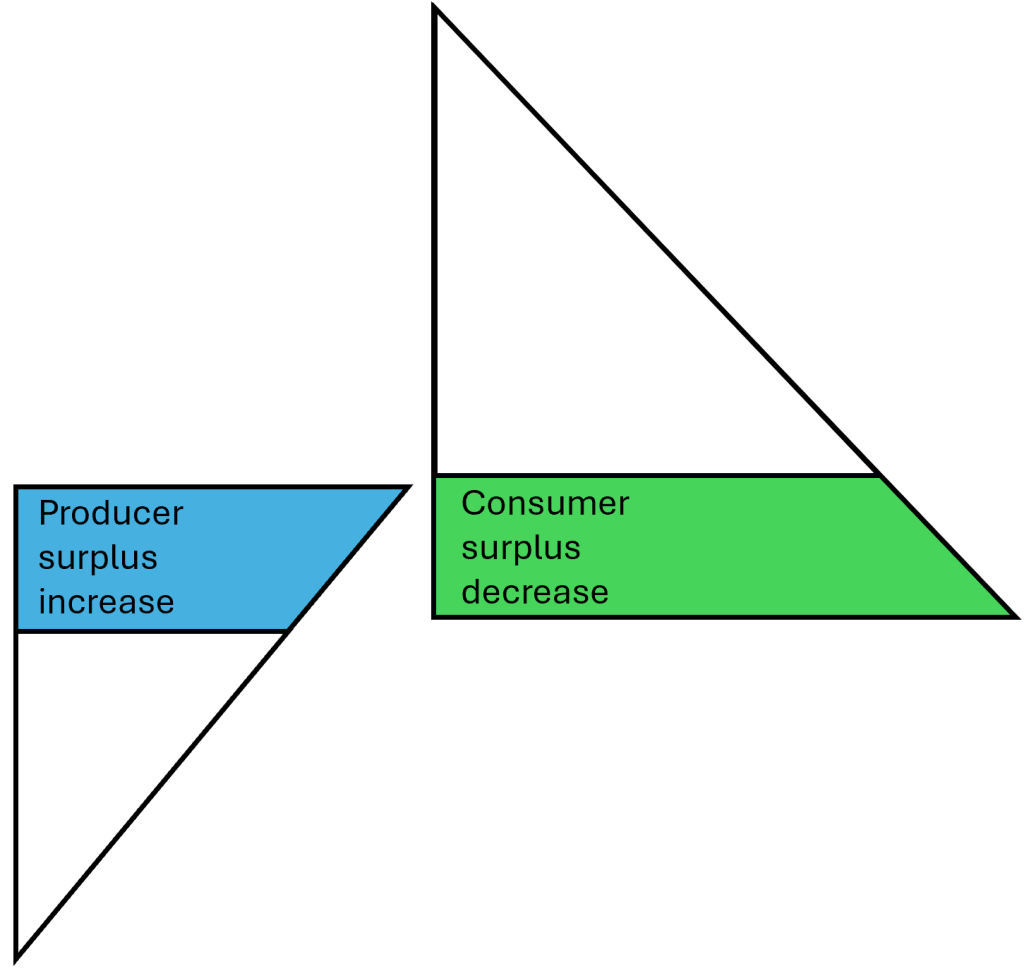

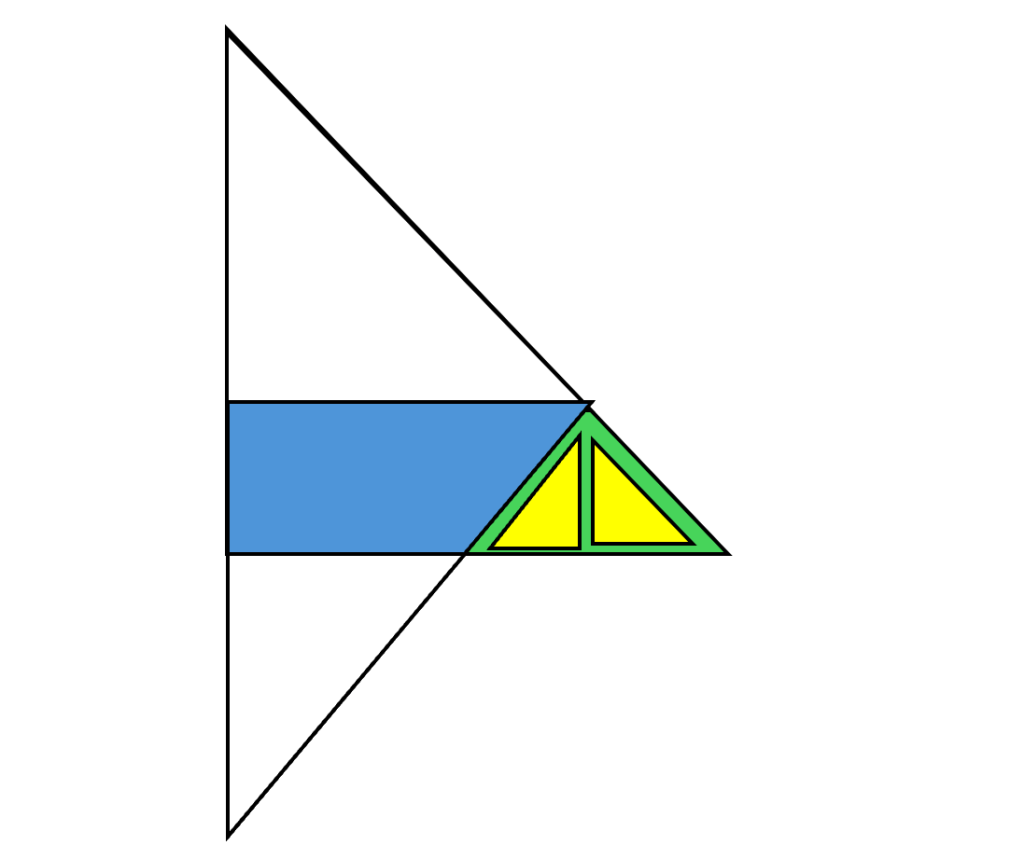

Did the consumer surplus grow more than the producer surplus shrank? If so, we have a net win for the overall wealth of our country!

Here’s a comparison (with some positional readjustment to more easily compare):

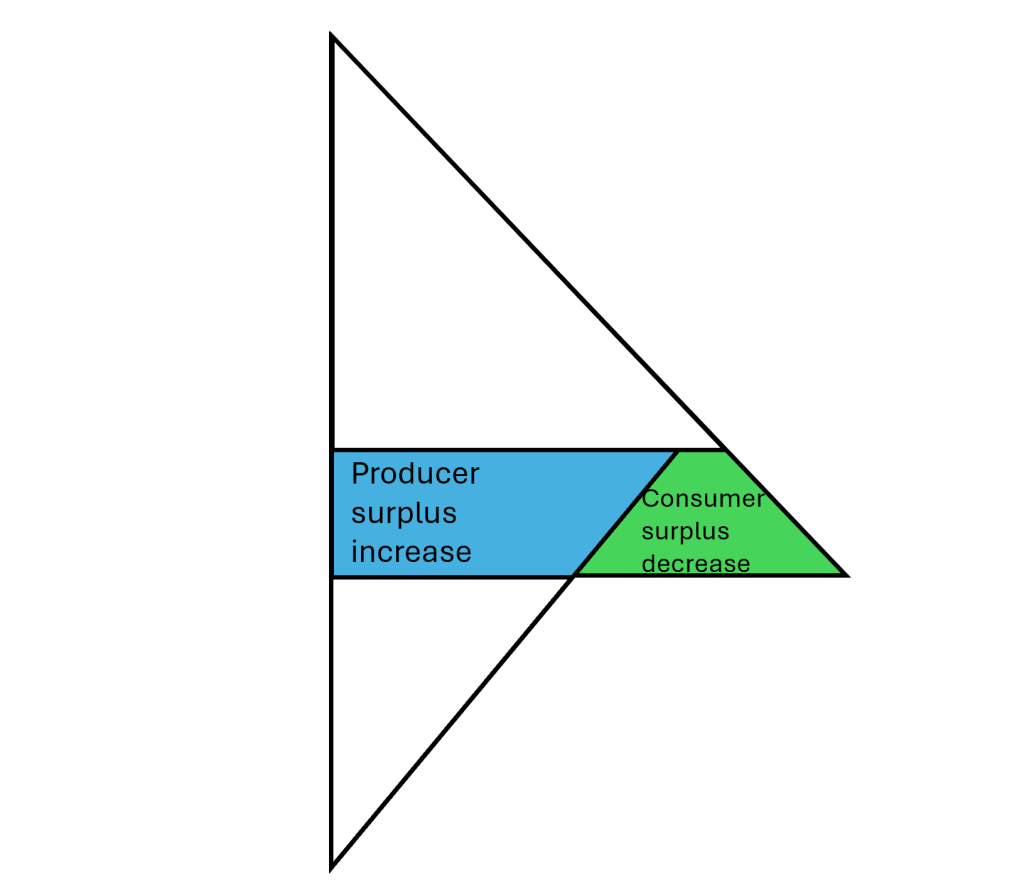

And here’s an overlay:

As you can see, there’s a good-sized net gain in wealth for the country because the consumer surplus increased a lot more than the producer surplus decreased.

In summary: With free trade, American consumers benefit a lot more than American producers lose.

This happens a lot with economics and public policy–a small benefit to everyone far outweighs the cost to a few.

This analysis applies to every industry in every country. Free trade is a huge source of additional wealth to any country.

Free trade is beneficial for other economic reasons, too. It improves international relations, which decreases the likelihood of war (which is nice because war is one of the biggest wealth-sinks). And it shifts the limited supply of labour in each country from relatively lower-value industries (i.e., the industries that are shrinking due to losing market share to international competitors) to relatively higher-value industries in that country, which allows wealth to grow faster over time due to a higher average productivity of workers worldwide.

But what if we analyze this free trade policy from a narrower perspective? Let’s only consider its impact on U.S. jobs. Its immediate effect was that domestic clothing producers used to be producing 200 units annually, and now they’re only producing 125 units annually. Free trade almost cut the American clothing industry in half from a production standpoint, and I suspect that would result in approximately half of the American clothing jobs going away to other countries.

As you can see, free trade can look really bad from a narrower perspective. But, remember–that’s a limited perspective. When you also take into account the benefit to domestic consumers, the net effect is a great increase in our country’s wealth.

This brings up a hypothetical worst-case scenario: What if all of a country’s industries are higher priced than its international competitors? Would that mean prices for everything would be really low but nobody would have a job?

No.

Reason #1: There are many goods (and even more services) that can’t be imported (for example, hair cutting, chefs in restaurants, electricians, etc.), so many jobs would still exist.

Reason #2: Remember the caveat I gave earlier about how the value of something is really what people use when they’re shopping for stuff. Even if the average price of goods coming out of a country are higher than the world price in every case, there would still be people around the world who think that certain products from that country are the highest value, so there would still be demand for that country to export all sorts of goods.

Reason #3: This is the most important one. You have to remember that the world is not a static snapshot. It’s a dynamic world where things change over time. And so how that country responds to this severe trade deficit (they’re importing a lot more than they’re exporting) depends on its regulatory environment and economic policies. There may be a time of high unemployment, but more realistically as certain industries shrink due to free trade, other industries would be growing, especially in a minimally regulated and capitalistic society. New companies and entire new industries would be created by entrepreneurs, and the country as a whole will shift its labour force into those industries that that country is particularly good at, and wealth will continue to grow for that country. However, if the country is a highly regulated and central-planning-based economy, the likely result of free trade-induced job losses is that the government would enact trade barriers (such as tariffs), thus slightly decreasing its unemployment rate in the short term and extending indefinitely its relative poverty in the long term. That’s what can lead to a situation where the government has to turn to increasingly totalitarian policies to prevent people from emigrating or, worse (from the totalitarian government’s standpoint), staying and blaming the government for their poverty.

To summarize my answer to this worst-case scenario: Free trade is still the best policy in the long run.

To some extent, that worst-case free trade scenario applies to the U.S., which has some of the most expensive labour and, thus, consistently higher prices than the world price. Fortunately, we are a pretty capitalistic society, and with the help of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), we’re (1) simplifying our regulatory environment and (2) releasing workers from a relatively unproductive sector (government jobs) so that they can instead find employment in relatively more-productive sectors (private jobs). Both of those changes bode well for the prosperity of America and for the unemployment rate as well.

And now I have one more little point to clarify about the above figures: How would free trade affect a country whose clothing price is lower than the world price?

The answer: Nothing much would change. Domestic producers would continue supplying the majority of domestic demand, so the free trade policy wouldn’t induce any significant job losses in that industry.

You could liken this to the car industry in Japan. The Japanese make some of the highest-value cars in the world, so it makes sense that the majority of cars sold in Japan are of Japanese make. In fact, out of the top ten car manufacturers (by market share) in Japan, all of them are Japanese. Thus, Japan’s zero-tariff policy for cars really has a minimal impact on the Japanese car market.

Now, let’s finally look at how the addition of a tariff would impact a country!

Here is the effect of adding a 40% tariff to our example of clothing:

As you can see, the world price is still $10, and the world-price-plus-tariff (Pt) is $14. At that new $14 price, domestic demand has dropped from 275 units annually to about 225 units annually. And of those 225 units, about 175 of them are provided by domestic producers, and the other 50 units are provided by foreign producers, as shown in Figure 7:

Things get interesting when we analyze how the tariff impacts consumer surplus and producer surplus:

And comparing that to the surpluses without the tariff:

And doing the same overlay as last time:

As predicted, there is an excess decrease in consumer surplus. In other words, the tariff hurt consumers more than it helped producers, so it was a net harm to the country’s wealth.

But wait! We have to consider the money the government earned in this because, remember, the government is earning $4 for every unit of clothing imported. Here’s how the government’s surplus (tariff revenue) would look if we highlight the area on the graph:

Just to make sure the interpretation of the size of that box is clear, remember that the government only earns tariff revenue on the 50 units imported, and it only earns the extra $4 that it’s charging on those units.

If I add the consumer surplus and the producer surplus back into the graph, here’s how it looks:

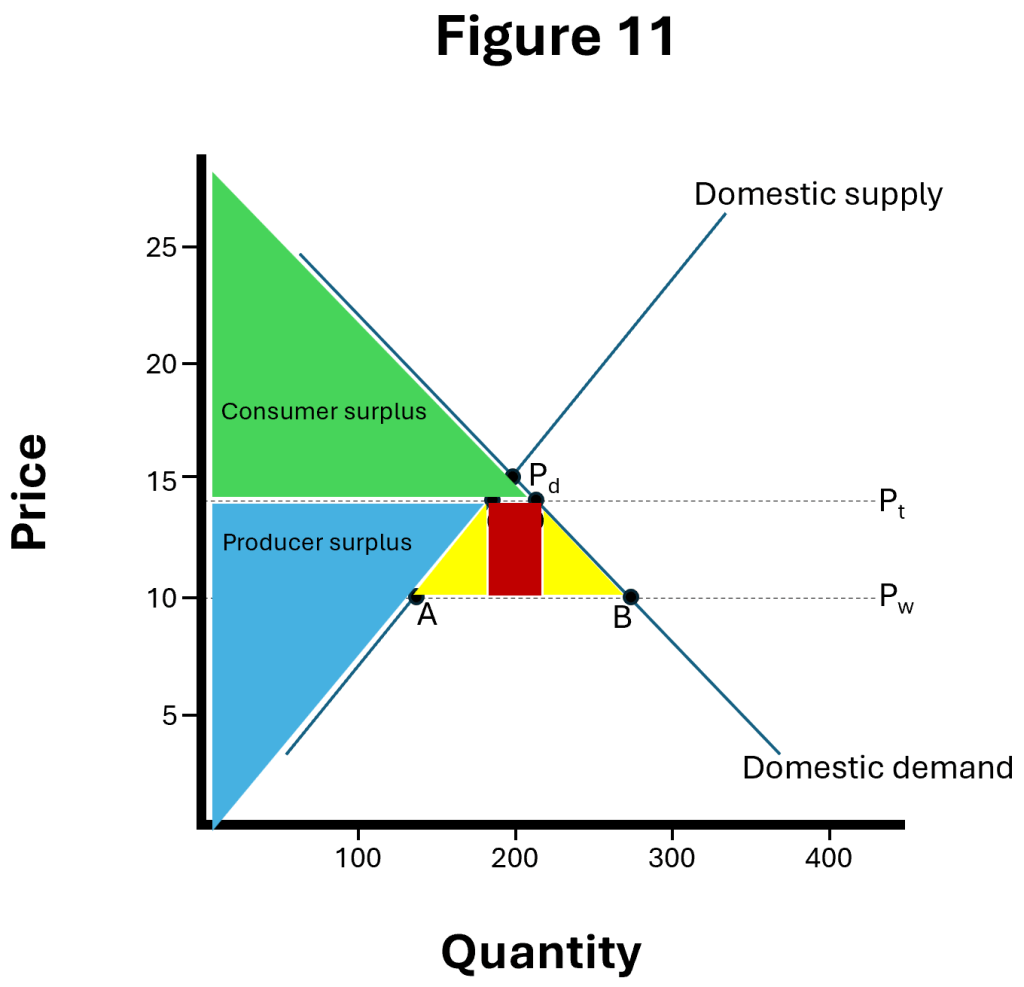

Do you see those two conspicuous empty triangles (to the left and right of the government’s tariff revenue) that used to be consumer surplus (see Figure 5) before the tariff was added? Here, let me highlight them:

Those yellow highlighted areas used to be consumer surplus, but now they’re not anybody’s surplus. It’s wealth that has been lost due to the tariff. We call it deadweight loss.

Before dismissing this as trivial, compare those to the benefit we gained from implementing free trade in the first place:

The tariff-imposed deadweight loss almost negates all of the benefits we originally gained from free trade.

[Feedback from one of you guys: In this example, the tariff-imposed deadweight loss was almost as large as the benefits originally gained from free trade, but the amount of deadweight loss a tariff causes can vary quite a bit depending on the slope and shape of the supply line and demand line (i.e., their elasticity functions), the size of the tariff, and also the difference between the world price and the domestic price. So, that deadweight loss could end up being only a small fraction of the size of the consumer surplus bestowed by free trade, or it could even be larger.]

I like efficiency because it brings greater wealth and improved quality of life. And I dislike deadweight losses because they make wealth evaporate and worsen quality of life. So this makes me pretty unhappy about tariffs.

But wait! Isn’t all of this negated by a variable I’m not taking into account? What about the claim that other countries are paying for that tariff?

Let’s look at exactly how the money flows. First, the U.S. government imposes a 40% tariff on imported clothing. The foreign producers have to pay this 40% of the price of their goods directly to the U.S. government when their goods hit our border. But foreign companies can’t simply absorb that 40% cost increase. Heck, most companies’ profit margins are way less than 10%. So they will have to raise their prices in response to that 40% tariff. If they raise their prices by approximately 40%, then what has happened is the foreign producer has paid the tariff directly to the U.S. government, but they are getting the extra money to pay for that tariff by charging higher prices. And who pays the higher prices? We do. American consumers do. We’re the ones buying the goods for $14 now instead of $10.

So, the definition of a tariff is that it’s a tax on imports, but the important thing to understand is that tariffs are not taxes on foreign companies; they’re indirect taxes on domestic consumers.

There is an argument that, in order to remain competitive after a tariff is implemented, foreign companies may be willing to take slightly less profit, so they would absorb a portion of the cost of the tariff by not raising their price by the full amount of the tariff. But this would only cover a small portion of the tariff because, again, companies are very limited on how much they can absorb cost increases.

This means that the claim that, “through tariffs, other countries will fund our government” is demonstrably false. The money the U.S. government makes from imposing tariffs will come from American consumers indirectly. Just like inflation, tariffs imposed by the U.S. government are an indirect (and, therefore, usually hidden) tax on Americans.

[Update 2/12/25: There are scenarios where foreign companies and governments can actually make that statement true. For example, I already mentioned that a company could choose to take a hit on their profit and not raise their U.S. price by the full amount of the tariff. Their government could facilitate that by subsidizing the company, thus replacing the lost profit and allowing the company to even continue selling their goods at the same price! In that case, you do in fact have the foreign government paying the cost of the tariff. I haven’t looked into data on this topic, but I suspect this only happens in a minority of cases. And, if it is happening, then it signals to the U.S. government that it can increase the tariff even further to take advantage of (maximize) this wealth transfer from the foreign government to American consumers.]

[Another update 2/24/25: Another factor I didn’t originally account for above is when the U.S. imposes a tariff on a country that is highly dependent on exports, especially to the U.S., how that can affect exchange rates. If a country is about to lose a large chunk of its economy, investment in that country will drop, as will the demand for that country’s currency. The result will be a devaluation of that country’s currency. So, for example, if a company raises the prices on the goods they’re exporting to the U.S. by the full amount of the tariff BUT the new exchange rate with that company’s country’s currency has changed to make products from that country cheaper, then the price increase is offset a little bit through us hurting their economy. I think this effect is unlikely to offset much of the cost of the tariff to American consumers, especially in the long run, but it’s worth mentioning because I hear the argument being made.]

Therefore, President Trump’s “External Revenue Service” turns out to be a misnomer and would be better named the “Deadweight Loss-Inducing Indirect Internal Revenue Service.” Or, the DLII-IRS for short. Nice, snappy.

Importantly, this doesn’t mean that tariffs are always the wrong choice, as I’ll get to. But if you’re going to support them on the basis of the claim that they will facilitate foreigners funding our government, your support is misplaced.

Ok, let’s review where we’re at.

We found that free trade enriches any nation that engages in it, in spite of the risk of a short-term decrease in jobs (or long-term decrease depending on the country’s economic and regulatory situation). And we found that tariffs obliterate most of those benefits gained by free trade (depending on how big the tariffs are).

What we haven’t done yet is summarize the impact on each party after tariffs are implemented, so let’s do that now:

American consumers: Large costs imposed on them by the tariffs because they are the ones losing surplus (in the form of benefits to American producers plus benefits to government plus deadweight losses).

American producers: Tariffs benefit them–they will sell more goods and earn more profits and create more jobs. But, again, these benefits are outweighed by the costs to American consumers.

One little extra tidbit about tariffs’ effect on American producers: I’ve only talked about the benefit tariffs give directly to the American producers whose competition has just become more expensive as a result of the tariff, but I haven’t mentioned the indirect (and often negative) effects a tariff can sometimes have on other producers. For example, if American companies are highly dependent on a foreign supplier because that supplier makes an input to the exact specifications the American companies need, and then that supplier gets hit with a tariff, it has raised the supplier costs for all those American companies, which can obviously have all sorts of negative effects. For simplicity, I will ignore this indirect effect of tariffs for the rest of the post, but I figured it was at least worth mentioning.

American government: Tariffs benefit them because they (1) earn more money and (2) also wins PR points if, in response to the tariff revenue, they decrease direct forms of taxation (such as income tax). This PR win hinges on the American people not realizing that they are still funding the government, only now it’s in the form of higher prices rather than direct taxes. And, unfortunately, because of the deadweight losses imposed by the tariffs, for the government to continue earning the same amount of revenue, the decrease in direct taxes can never be as large as the increase in prices.

Foreign companies: They will sell fewer units and, thus, probably lay off some workers. This means that there will be a net shift of jobs from their country to the U.S. as a result of the tariff. They may also end up making less profit per unit sold if they choose to lower their prices to remain competitive in the face of the tariff headwind.

[Update 3/25/25: Another argument I’ve been hearing lately about tariffs is that they will induce foreign companies to invest in new production capacity in the U.S. to avoid having to pay the tariffs. This is just another way of saying what I’ve already said above: After a tariff is instituted, domestic supply increases. Whether that increase in domestic supply comes from domestic companies increasing capacity or foreign companies increasing capacity in the U.S., the result is the same–we have more jobs in the U.S. and more of our products are being supplied by stuff that was produced domestically. The one benefit of foreign companies doing this, though, is that it is increasing foreign investment into the U.S. But foreign investment also means the profit they earn gets sent back to that foreign country, so, in the long run, it’s siphoning wealth from the U.S. When you have this nuance in mind, the individuals arguing that “foreign companies will start making huge investments into the United States” actually start to sound pretty ignorant. This is yet another reminder that a rich and/or intelligent thought leader who speaks with confidence and is trusted by millions can be totally wrong, and I believe that happens even more often when that thought leader’s tribalism leads them to not be critical enough of claims made by their tribe.]

Do you remember way at the top of this article, in the title, where I said that tariffs can be good?

Yes, tariffs can make sense if they are used for reasons other than to “make other countries fund our government.” Let’s review a few cases where they can make sense.

Tariffs Can Be Good Reason #1: Tariffs can make sense when they are used as a threat to punish behaviour we don’t like. As should be clear by now, the main punishment a tariff inflicts is stealing their jobs (i.e., shifting some jobs from their country to ours).

What kind of undesirable behaviours would justify threatening a tariff? One example would be when neighbour countries are not doing enough to help prevent drugs from being smuggled across our borders because of lax border control. Another would be when countries allow infringements on American intellectual property.

The hope is that the tariffs will not be imposed–only threatened–because, ultimately, as I have shown, the tariffs will also financially harm Americans. But, sometimes the benefit we could gain from a tariff (in the form of motivating policy changes in the other country) justifies the cost to ourselves, assuming the tariff works sooner or later to bring about the desired changes.

Before moving on to reason #2, let’s explore just a bit further how much our tariffs could hurt other countries, which would impact how powerful our threat of tariffs would be.

Let’s say that 50% of a country’s economy is built on exports by its clothing industry. If the U.S. only represents 10% of that country’s clothing sales, and we impose a large enough tariff on their clothing exports to us that it shifts half of those sales over to American producers, we have just cost that country approximately 5% of its clothing jobs, which would be 2.5% of its total jobs in the economy. That’ll hurt, but it’s something they could weather.

But what if America, as a huge and wealthy country, represents 60% of that country’s clothing sales? Then, if we impose a tariff that shifts half of those sales over to American producers, it will cost that country 30% of its clothing jobs, which would be 15% of its total jobs in the economy. That would be devastating.

So, a tariff will certainly hurt America’s wealth, but it can hurt other countries much more, especially when (1) the country’s economy relies heavily on exports and (2) the U.S. is a major purchaser of those exports.

Tariffs Can Be Good Reason #2: Tariffs can also make sense if they are used to diversify critical supply chains.

For example, do we really want to be dependent on China for all of our microchips and Russia for a large percentage of our fossil fuels? Imposing tariffs on such national security-critical products can help boost domestic production of those products, which makes us less dependent on other countries that could potentially cut off our supply of critical products.

Having said that, a more efficient way to achieve this might be through direct industry-wide subsidies, which would avoid the deadweight losses that tariffs incur. But, when a government chooses subsidies rather than tariffs, it doesn’t get additional revenue and the potential PR wins that tariffs offer; instead, it would just be spending more money, and it might have to raise taxes to do so.

Therefore, even though subsidies probably make more sense than tariffs to help us diversify critical supply lines, governments are much less motivated to use subsidies to do so.

[Addendum as a result of a comment from one of you guys 2/15/25: Subsidies have their own set of problems that I didn’t adequately acknowledge. One is that they tend to stick, and then the training wheels never come off and the domestic industry becomes inefficient and uncompetitive compared to the global marketplace. Another is that oversubsidization for a long period of time can force many of the global competitors out of business, creating undue consolidation and even a global dependency, which can be especially bad if the subsidization goes away suddenly and other countries have to scramble to develop domestic production capacity. None of this should be news–all government interventions in markets have the capacity to do more harm than good. And that applies to subsidies, too. This is why I tend to be a minimalist when it comes to government interventions in markets, but appropriately regulating markets to improve the incentives in them, if done properly and not under the influence of special interests, can be a very important way that governments help markets.]

Tariffs Can Be Good Reason #3: Sometimes temporary tariffs can be helpful to foster fledgling domestic industries. This is similar to reason #2, only the purpose is different.

In this case, the government is making a bet on a fledgling domestic industry. It thinks that that industry, if given a little boost in the form of protection from competition early on, will be able to grow and become efficient and also competitive in the world market, all of which would bring great wealth to the country.

But, again, the tariff should only be temporary. Once the fledgling industry has gotten off the ground, the tariff should go away.

So the hope with this type of tariff is that the cost imposed on the country’s wealth during the time the tariff was active will be more than made up for by the wealth brought in by that new wealth-generating industry it helped foster.

Tariffs Can Be Good Reason #4: Let’s talk about retaliatory tariffs.

Should the U.S. impose/increase tariffs on countries that impose them on us?

It depends.

To explain the answer, let me introduce a new term. I’ll call it “tariff damage potential.” This will specifically refer to how much damage a tariff can impose on the other country’s economy. We know that a tariff has a guaranteed and predictable harm on ourselves, but the tariff damage potential only refers to its effect on the other country. And while the damage a tariff imposes on your own country’s wealth is fairly predictable, the damage it imposes on the other country can vary widely and is mostly dependent on (1) how much that economy relies on exports and (2) how big of a trade partner the U.S. is to that country.

Therefore, if the U.S. buys a large percentage of a country’s exports, and their economy is heavily dependent on exports, our tariffs on them have a huge tariff damage potential, which I already demonstrated above in the “Tariffs Can Be Good Reason #1” section.

And this idea works both ways. If the U.S. economy were highly dependent on exports, and if a certain country is one of our huge buyers, then that country’s tariffs against the U.S. also have a huge tariff damage potential.

So, deciding on the best course of action when another country imposes tariffs on us comes down to comparing our tariff damage potential to theirs. If our tariff damage potential on them is greater than theirs is on us, then it makes sense to impose retaliatory tariffs.

Let’s look at an example to illustrate this.

What if the Motherland (Canada) drinks too much beer and, in its drunken stupor, decides to impose a 25% tariff on all products from the States? And, in response, the U.S. imposes a retaliatory tariff of 25%. Canada has started a “trade war.”

Since Canada’s economy is more dependent on exports than the U.S.’s, and since Canada exports 77% of their total goods to the U.S. and the U.S. exports only 18% of its goods to Canada, you can see how this will go.

I’m not sure concrete numbers to calculate what the net shift of jobs would be from Canada to the U.S. would make my point any clearer, especially because of the extensive assumptions I would have to make (since I’m not equipped to do econometric analyses), but it’s safe to say that Canada would be hurt by the U.S. tariffs a lot more than the U.S. would be hurt by Canada’s, meaning there would be a sizable net shift of jobs from Canada to the U.S. So this would be a situation where retaliatory tariffs would make sense.

The principle here is that we should always impose retaliatory tariffs if our tariff damage potential is greater than theirs, with the specific goal of discouraging other countries from imposing tariffs on us. And since the U.S. (1) is not as highly dependent on exports as most wealthy countries are and (2) has the largest economy in the world, I suspect retaliatory tariffs will make sense with every major trading partner we have.

But, if there’s a rare case where our tariff damage potential is smaller than theirs, then the right response is not to impose retaliatory tariffs. Instead, we just have to keep relying on capitalism and a minimal and simple regulatory environment to continue growing our wealth. And, if we end up growing faster than the tariff-imposing country and, as a result, our tariff damage potential grows larger than theirs, then we impose retaliatory tariffs.

But, importantly, what would be best for everyone would be free trade! So retaliatory tariffs should always be conditional. In other words, they should always come with a promise: If you eliminate your tariffs on us, we will eliminate ours on you.

From a game theory standpoint, I think the best policy for the U.S. is to commit to imposing conditional retaliatory tariffs on every trade partner whose tariff damage potential is smaller than ours, and we should make that policy very well known. That way, any trade partner will know that, from this point forward, imposing tariffs on us (or continuing pre-existing tariffs) will hurt them a lot more than it will hurt us. And that will force our trading partners to weigh that guaranteed cost carefully before choosing to impose tariffs on us. The end result would likely be fewer tariffs between us and our trading partners, which is really the goal here.

With all this information in mind, it’s pretty strange that Prime Minister Trudeau recently threatened to impose a retaliatory tariff on the U.S., justifying it by saying that he’s sticking up for Canada. Such a policy is not likely to hurt the U.S. enough to make President Trump back off from his tariff threat, so it would probably only hurt Canadians further.

Before concluding, there’s one more argument about tariffs that I want to respond to.

I see many people arguing that tariffs are good based on historical trends. For example, sometimes they reference the U.S. in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when the government relied heavily on tariffs for revenue and there was strong economic growth. They see that there was huge GDP growth during that time, and they assume it was because of the tariffs. Other people will argue that such-and-such good had a tariff imposed in such-and-such year, and it didn’t make the price go up.

There are situations that I’ve explained above that could account for a tariff not making a price rise, depending on what the world price of the good is compared to the domestic price. But, that aside, the important thing to recognize here is that each of those arguments are based on a fallacy: seeing a correlation and assuming causation. For example, when a tariff is implemented and the price doesn’t rise, rather than assuming that means tariffs don’t induce price increases, try looking into other factors that could have occurred at the same time to offset the price-increasing effect of the tariff. And here’s another example: If America’s GDP grew quickly during a time of high tariffs, rather than assuming the GDP grew quickly because of the tariffs, maybe look at other factors from that time period to figure out why GDP grew quickly during that time, which may lead you to wonder how quickly GDP could have grown had tariffs not been inducing so many deadweight losses during that time period.

The economic principles that I’ve laid out in this post are well established, and if someone wants to make a contrary argument based on historical anecdotes or assumed causation, they have the burden of proof to explain and demonstrate precisely what causal mechanism their argument is based upon. And, if they can successfully do that, then we’ve learned something new and can now more accurately understand and predict the world! And that allows us to make better policies moving forward, which will improve lives. Winning, all around.

In conclusion, how would I sum up this lengthy post?

Maybe I would just say this:

Tariffs interfere with free trade, so they decrease the overall wealth of any country that imposes them. But there may be situations where there is a large enough potential benefit to justify them, including the four reasons I listed above (and I acknowledge that there may be others I haven’t thought of). But we need to be really deliberate about identifying those potential benefits and weighing them against the guaranteed costs before we ever impose a tariff.

What’s best for American consumers? No tariffs.

What’s best for American producers? They may want tariffs to help boost their sales, but I’d prefer we take off the training wheels and let them compete in the global market, which will ultimately be better for everyone.

And now, as a reward for those who got all the way to the end of this post, I will share my two favourite comments I received on X in response to sharing some of these details about tariffs:

People on the internet are just so entertaining! I try not to troll, but it’s very tempting sometimes.

I don’t think this statement is necessarily correct:

“The tariff-imposed deadweight loss almost negates all of the benefits we originally gained from free trade.”

I completely agree that tariffs necessarily create a deadweight loss but we don’t know how it will compare with the benefits of free trade without knowing the magnitude of the price increase resulting from the tariff and the steepness of the supply and demand curves (i.e. their elasticity). You can come up with scenarios where the impact of the tariff is very small compared to the benefits of free trade or very large. I am not making a strong claim here; for instance we would readily agree that a trivially small tariff (e.g. 1 cent on an imported car) has not negated most of the benefits of free trade for that item.

Please don’t take this as disagreeing with the overall point that tariffs are a tax on consumption and like all taxes they create market inefficiencies and deadweight losses. Ironically, we had tariffs on steel in 2018 at 25% which continued in the Biden administration yet a foreign steel firm, Nippon Steel, was in a much healthier state than either US Steel or its other would-be suitor, Cleveland Cliffs, when their takeover bid became a political football last year.

You make a really good point. It’s something I will update in the article itself. Thank you for the feedback! Also, interesting example with Nippon Steel–it shows how the U.S. government imposing a tariff doesn’t necessarily lead to the foreign company becoming weak.