If you haven’t noticed already, I have a strong interest in political philosophy. Isn’t thinking about the different ways government could be designed exciting? This is primarily a health policy blog, but political philosophy topics are closely enough related to what happens in healthcare that I write about them here as well.

I recently read (listened to) The Road to Serfdom by Friedrich Hayek. The interesting thing is that he seemed to be using my framework for categorizing governments. So I’d like to restate his main points in the context of my framework.

The book was written during WWII and published in 1944. At that time, he was living in the U.K., and he was seeing a movement there toward central planning, so he wrote this book to explain to the people involved in that movement how central planning starts a country down a road that leads to totalitarianism. He used Germany’s then-recent political history as the main case study to show how that process goes.

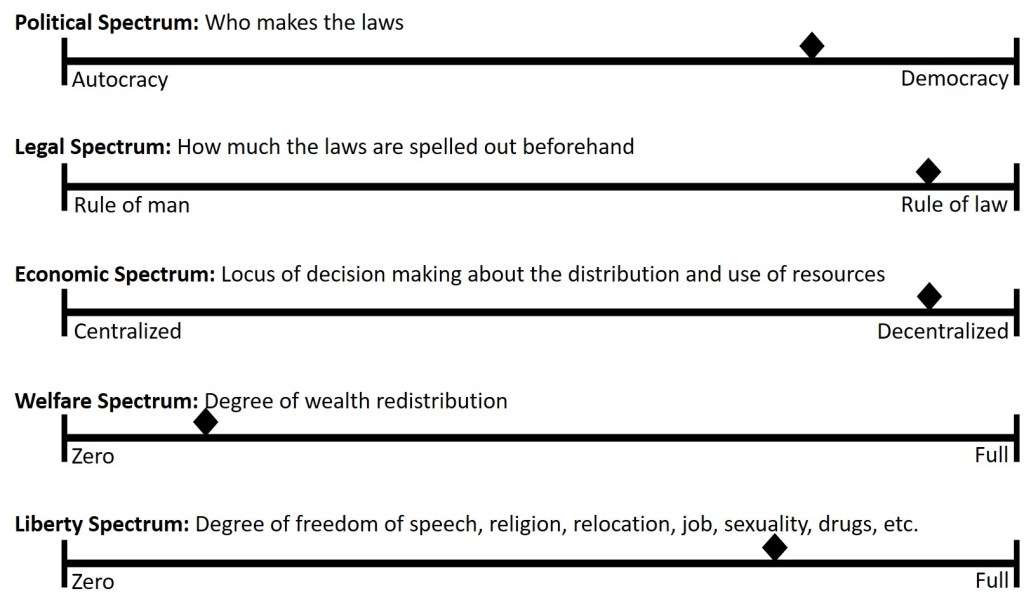

Let’s say the U.K.’s government looked something like this at that time:

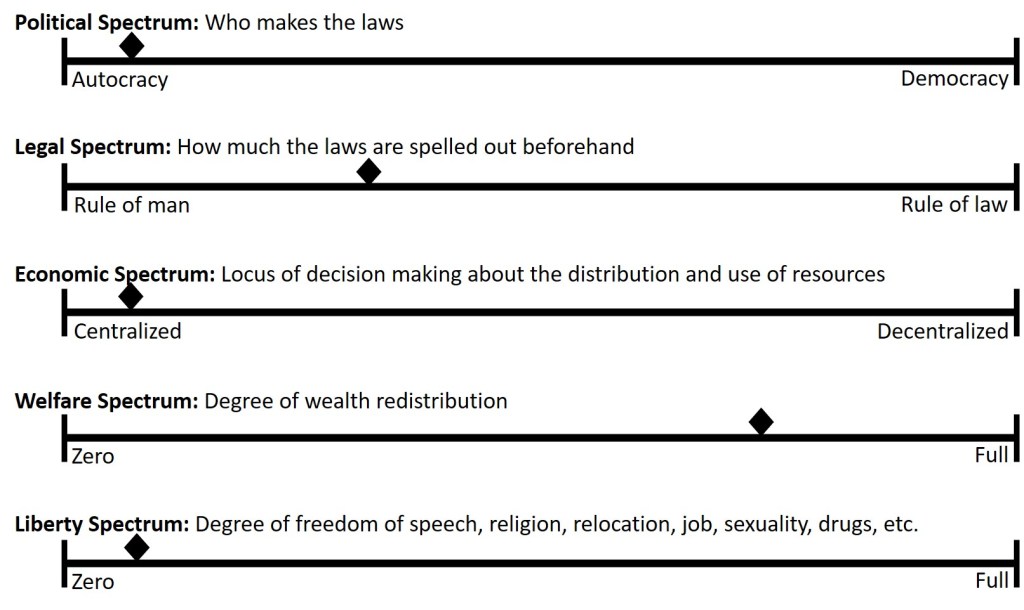

And the “planners,” as Hayek calls them, wanted to do this:

There were different motivations for this. One was that, at the time, technology was seen as necessarily pushing industries toward monopolies, so they felt that government ownership would limit the tyrannies of monopolies. Another motivation that developed is a change in how freedom was conceptualized. “Before man could be truly free,” they said, “the despotism of physical want has to be broken.”

Notice that these are not totalitarian desires; they are desires for efficiency and an increase in freedom and opportunity for the poor. So how does Hayek say they lead to big leftward shifts on the other three spectra?

He doesn’t exactly provide a super explicit stepwise process, but here are some of his major checkpoints along that road:

- Planning a society will involve areas with great agreement, but there will also be areas with great disagreement. In those areas of disagreement, people lose the freedom to conserve their preferences.

- If a state owns half the economy, it necessarily controls most of the other half indirectly due to the interactions between industries, such as through shared inputs to those industries (like labor and resources). This means there is no part of society where people are completely free of government direction.

- After a democracy votes in a planning government, they find that the democratic process is ill equipped to handle the plan’s requirement for rapid and unified-purpose decision making, so different parts are working at odds with the overall plan or are slow to change to fit better. For this reason, the laws they pass increasingly delegate decision-making power to unelected experts. Eventually, their legislative power becomes limited to making decisions about the plan’s overall goals, although in this area as well they find themselves inadequate because frequent shifts in goals (due to differences in factions’ priorities and politician turnover with each election cycle) undermine progress toward any ideal. Thus, they begin to concentrate the power to direct the overall goals (and coordinate the efforts of those many boards of experts) into a single individual who is not fettered by democratic and legislative processes.

- This new powerful leader is occasionally confirmed via the democratic process, but the leader has the power to ensure, one way or another, that the votes go in his direction so he can continue working toward the ideal society.

- A planned economy becomes the rule of man because so many of the decisions about people’s lives become arbitrary (whose interests to prioritize over whose). For example, do you increase wages of the working poor who are struggling to get by or do you decrease unemployment?

- A planning government only sets out to control and improve the economic aspect of people’s lives, but by controlling the economic aspect they are indirectly controlling nearly every other aspect, such as where people live (you can’t move somewhere else if the government hasn’t decided there will be jobs available in that area) and what you do for fun (which luxury items and entertainment options are available and how they are priced).

- People are dissatisfied when they are made to go along with another’s set of priorities and values, so the government creates indoctrination tools that will reduce the number of people resisting their goal for an ideal society.

- The whole apparatus of information, including schools and print and audio and visual media, will be used not only in supporting the ends but also the means to achieve the ideal society, and speaking out against it becomes not just an opinion but treachery.

- The leaders who tend to arise in such a system are those who are the strongest and most motivated to get things done, which means they are the most likely to be willing to ignore negative impacts on other people in pursuit of their singular focus (the means justify the ends).

So this is where the U.K. could have ended up if the planners had gotten their way, and remember this would all come from the planners’ initial desires to have the government help out with inefficient industries and to reduce the despotism of poverty:

There are so many other points made in the book that flesh out these ideas more fully, but I will forbear. Suffice it to say that end point of the the road is not just totalitarianism, but serfdom, which is due to the increasingly impossible task of a government trying to control an entire economy and, in the process, distorting every single worker’s incentives away from efficiency and innovation and redirecting resources away from their most profitable uses.

Reading this was quite an interesting experience because, with every point Hayek made, I could visualize which spectrum he was talking about and interpret his explanations in terms of which direction (and how far) a country would slide along that spectrum.

And the question it left me with is this: If Democrats’ policies tend to push toward more wealth redistribution and more government control over industries (e.g., Medicare for All), does this mean electing Democrats puts us on the road to serfdom?

My thought is that it doesn’t. Pushing for Medicare for All is not the same as endorsing a planned economy. One could argue that it’s one step closer to getting us on that road, but we have seen “social democracies” in Scandinavia not progress toward totalitarianism, so maybe that slope isn’t as slippery as Hayek makes it out to be. Exactly which factors would also need to be at play for us to truly get onto the road to serfdom? I don’t know. Any thoughts or ideas are welcome.

Very nice analysis! I like yours better than mine at FixUSHealthcare.blog: http://fixushealthcare.blog/2018/10/26/single-payer-healthcare-is-socialism-why-thats-wrong-wrongheaded/

Two further reflections on this topic:

1. Hayek certainly was suspicious of unchecked government power, including that exerted through economic means. But he was by no means a Nozick-style extreme minimalist-government libertarian. Here is an excerpt from his Wikipedia entry:

The role of government

Although Hayek believed that government intervention in markets would lead to a loss of freedom, he recognized a limited role for government to perform tasks of which free markets were not capable:

The successful use of competition as the principle of social organization precludes certain types of coercive interference with economic life, but it admits of others which sometimes may very considerably assist its work and even requires certain kinds of government action.[28]

While Hayek is opposed to regulations that restrict the freedom to enter a trade, or to buy and sell at any price, or to control quantities, he acknowledges the utility of regulations that restrict legal methods of production, so long as these are applied equally to everyone and not used as an indirect way of controlling prices or quantities, and without forgetting the cost of such restrictions:

To prohibit the use of certain poisonous substances, or to require special precautions in their use, to limit working hours or to require certain sanitary arrangements, is fully compatible with the preservation of competition. The only question here is whether in the particular instance the advantages gained are greater than the social costs they impose.[29]

He notes that there are certain areas, such as the environment, where activities that cause damage to third parties (known to economists as “negative externalities”) cannot effectively be regulated solely by the marketplace:

Nor can certain harmful effects of deforestation, of some methods of farming, or of the smoke and noise of factories, be confined to the owner of the property in question, or to those willing to submit to the damage for an agreed compensation.[30]

The government also has a role in preventing fraud:

Even the most essential prerequisite of its [the market’s] proper functioning, the prevention of fraud and deception (including exploitation of ignorance), provides a great and by no means fully accomplished object of legislative activity.[31]

The government also has a role in creating a safety net:

There is no reason why, in a society which has reached the general level of wealth ours has, the first kind of security should not be guaranteed to all without endangering general freedom; that is: some minimum of food, shelter and clothing, sufficient to preserve health. Nor is there any reason why the state should not help to organize a comprehensive system of social insurance in providing for those common hazards of life against which few can make adequate provision.[32][33]

He concludes: “In no system that could be rationally defended would the state just do nothing.”[31]

2. What puts a society on the road to serfdom? Here’s a thought on how to approach the answer: Serfdom = economic/political dependence = tyranny. That is, this is not about economics (alone), but rather about power, exerted through various means. Timothy Snyder’s recent small monograph On Tyranny talks about the “road to tyranny” in a different way.

Bottom line: I agree with your conclusions that Medicare-for-all is not “central planning.” And that a social safety-net does not necessarily undermine a “free market” but rather can serve as a corrective, which calibrated properly can shore up the capitalist “free market,” for example putting purchasing power into the hands of those who will spend.

Yes, I think Hayek holds the same position that most do in the U.S.A.–they feel like we’re a wealthy enough country that there’s gotta be a way to share with others. The issue, though, is finding a way that will satisfy conservatives’ concerns about the economic inefficiencies and adverse incentives that are so often created by such programs. From an economic efficiency standpoint, avoiding administrative pricing is crucial. From an adverse incentives standpoint, avoiding welfare cliffs can be helpful but is only a tiny start.