Today I learned about a doctor group in Ohio that is advocating for a law to eliminate insurance companies’ wanton (and almost unrestricted) refusal to deny reimbursement for various health services. I applaud these efforts; but, I think their focus would lead me to categorize them as bariatric surgeons of the health system.

Today I learned about a doctor group in Ohio that is advocating for a law to eliminate insurance companies’ wanton (and almost unrestricted) refusal to deny reimbursement for various health services. I applaud these efforts; but, I think their focus would lead me to categorize them as bariatric surgeons of the health system.

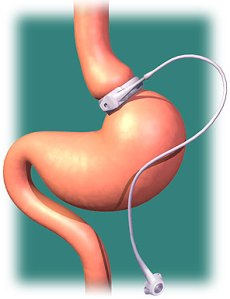

Bariatric surgery, A.K.A. weight-loss surgery, is criticized as (to reference Thoreau) hacking at the branches of evil rather than striking at the root. The root cause of obesity (in most cases) is a suboptimal diet and insufficient exercise. But, instead of going through painful lifestyle changes to solve the root of their obesity problem, people can now get bariatric surgery instead. (I should say here and now that I don’t think bariatric surgery is all bad–it has its uses, many of which are wonderful and important, as do advocacy groups such as the one spoken of above.)

How does this relate to the work being done by that noble doctor group in Ohio? They’re trying to contain the ill effects of an underlying incentive in the health system rather than change that underlying incentive that is causing insurance companies to seek every way possible to limit medical loss. (“Medical loss” is the term health insurance companies use to refer to their money they spent on paying healthcare providers for services rendered.)

What is this underlying incentive that insurance companies are rationally (yet probably unethically) responding to? They get paid more for spending as little as possible on health care. Instead, they need to get paid more for keeping patients healthy. If that incentive were to be changed, the whole issue of reimbursement denials would be solved.

Even “pay for performance” is another, more sophisticated form of health-system bariatric surgery–providers would naturally invest much more time and effort (e.g., investing in EMRs, crafting policies to help physicians more closely adhere to clinical guidelines, perform research in ways to reduce complication rates and hospital re-admissions, etc.) to find every possible way to keep patients healthy if it meant they would be more profitable as a result of it.

So, how can a payer get paid more to keep patients healthy? Integrated systems. Capitation. There are ways, but this post isn’t about the solutions so much as it is about understanding the causes of the problems. Sorry.

UPDATE: Another way to look at this would be using the carrots and sticks metaphor. Right now, our main way to negate the ill effects of bad underlying incentives in healthcare is by using sticks to punish the natural responses to the incentives the system provides. Using sticks is prone to getting “gamed” (i.e., people find ways to avoid the punishment without actually doing the desired action). Carrots, on the other hand, provide good underlying incentives (assuming the carrot is well-aligned with what we really want health-care providers to be doing for us), and they stimulate creativity to find more effective ways to get them.

Your blog is interesting although it asks more questions than it answers – not that that is bad. You write almost exclusively about the US system but as a Canadian you undoubtedly have had some experience with their medical system. Given that we spend a greater percentage of our GDP in health care and given that it’s growing more rapidly than inflation, shouldn’t there be some lessons to be learned from other countries that cover their entire population at a lower cost than the US? I would be interested in your comparative views.

Also, here are a couple of interesting links that you may have seen: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2009/07/24/a-modest-proposal-on-payment-reform/ and

http://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/what-does-all-payer-really-mean/. They don’t deal with your post exactly but are interesting things to read.

I agree–I do spend very little time on answers . . . so far. As I mention in one of my early posts, I am first concerned about thoroughly understanding the root causes of problems; without that, I can’t say a thing about how to solve the problems because I don’t even know what’s causing them. I’ll check into the links you sent, think a little on your question, and either write a post or email you directly.

Here’s another question. Although the focus the past several weeks has been on the debt ceiling and the subsequent deal that raised the ceiling cut future government spending, the reality is that the major problem with future govenernment spending is due to increased Medicare costs. Many of the proposals aimed at lowering Medicare costs are really just cost-shifting from the government to the individual – after all, if the decision is to reduce the amount of premium support by the government for the individual and no attempt is made to manage the growth in medical costs, an increasing burden will fall on the individual. Now I’m 55 years old and the effect of this will likely be less on me than it will be on you and your generation. Nonetheless, the apparent lack of popular support for the Affordable Care Act, (which aimed to “bend” the cost curve, a seemingly rational approach) and the push back from the mandate part fo the Act (who doesn’t want health insurance?) both seem like irrational responses to the health care crisis we face. But most approaches protect the people either already in the program or close to the age of eligibility at the expense of younger folks who have a long way to go.

What I wonder is: why would younger people such as yourself accept this tradeoff? Is it because the length of time until you are eligible is so far off you are unable to appreciate the importance of that benefit? After all, if medical costs continue to outpace inflation, it will be almost impossible to save enough to cover the gap between what Medicare covers and the cost of healthcare for the individual. Or is it that your generation doesn’t believe that Social Security and Medicare will be there when you retire so you are willing to cut benefits – assuming that they will have no value anyways? Another question for Americans is whether they believe healthcare is a human right or a privilege. As a practical matter, I believe it would be less expensive to provide universal healthcare than our current system of limiting access and them dealing with uninsured and sicker patients later (I believe Taiwan went from a healthcare system similar to the US to a universal healthcare plan and their costs where pretty similar while covering 25% more of the population).

“What I wonder is: why would younger people such as yourself accept this tradeoff?”

A couple of thoughts on this question. First, your assumption that young people accepted the tradeoff you described in the earlier paragraph is a flawed one. In general, young people are not involved in the political system, older individuals, that are receiving Medicare and SS benefits, are. This is a big part of the reason why long-term concerns are ignored for the sake of short-term political expediency. By the time that my generation nears retirement, all the policy makers will be out of office.

Most young Americans aren’t really paying attention to how social policy is changing in the United States, and it is changing mightily right now.