In Part 1, I talked about the origin and purpose of money and also how new wealth is introduced into a society. This week, I want to talk more about how wealth transfers from one person to another.

As I explained before, new wealth is always being generated using the land + labor combo (i.e., the natural resources from the earth combined with human labor produces new wealth). We could call the people doing this work the wealth-from-the-earth-gleaners (or maybe wealth-gleaners for short).

Wealth-gleaners are the original owners of all wealth in society, and then they distribute that wealth to others in exchange for the goods and services they want. In this way, the wealth of a society is both generated and distributed.

I don’t want you to assume that just because someone is the original generator/owner of wealth that it means they will automatically be wealthier than all others. Think about a farmer working a particularly infertile plot of land. He may be only generating just enough wealth (in the form of crops) to have a roof over his head and clothes on his back and food on his table, with nothing to spare. This is what Adam Smith called a “subsistence wage”–when you’re earning just enough wealth to continue subsisting. This farmer’s wealth, as limited as it is, will still be distributed to others in society when he buys things he needs from them, such as clothes or a re-thatched roof. So you see that he is a source of wealth in society but also that doesn’t make him richer than non-wealth-gleaners.

An interesting effect of wealth-gleaners being the original generators of new wealth in societies is that a society’s growth of total wealth is limited by how much these wealth-gleaners are generating and introducing into a society. (This assumes no trade with outside societies–that will be added in later.) So, if you want the total wealth of a society to grow quickly, you want a ton of wealth-gleaners. Or, if that’s not what the society’s economy needs, then you at least want the wealth-gleaners your economy to, on average, be generating a lot of wealth. If they’re doing that, they will be generating way more than just bare subsistence wealth for themselves, so in this case they would be rich!

Ok, now that I have talked so much about the generation of wealth, the time has come to introduce an idea that I will use regularly throughout the rest of this series. I’ve invented a way to quantify a standard unit of wealth.

*Trumpets sound*

I hereby define a new standard unit of wealth. It will cleverly be known as a Wealth Unit (WU), calculated from the average amount of wealth that can be obtained by one hour’s worth of unskilled, low-risk, average-physical-intensity work.

Let me explain that a little bit. One WU could mean an hour’s worth of a farmhand picking fruit from the orchards, or it could be the blacksmith’s assistant carrying wood for the forge and pumping the bellows, or any other labor of that ilk. If the work is especially onerous and/or dangerous and/or if it requires training and expertise, then one hour of work could generate more than 1 WU. And if it’s super easy work, it could generate less than 1 WU/hour. This should all be obvious–when I work as a physician, I make more money per hour than when I worked at Costco as a teen checking receipts. And whether a laborer is paid per hour or per project or per year (i.e., a salary), it can all be converted to an hourly wage.

One important use of this idea of a Wealth Unit is that it can quantify the cost of production of anything. If a blacksmith’s time is worth 4 WUs per hour (he is very skilled), and it takes him 1 hour to make a cook pot, the cost of labor that went into that cook pot is 4 WUs. And if the cost of the metal plus the depreciation of his shop plus cost of wood for the forge plus cost of his assistant’s time etc. all totaled to be 2 WUs, then he will break even (i.e., his time will be adequately compensated) if he exchanges the cook pot for something else worth 6 WUs. If he sells it for 7 WUs because this pot turns out especially beautiful and round, then, after subtracting the costs of 2 WUs, he has earned 4 WUs for his time and also earned a profit (as the business owner) of 1 WU. Now you see the difference between being a worker (getting paid a fair number of Wealth Units for each hour you work) versus being a business owner (getting the profit that the business makes).

The beautiful thing about WUs is that their value remains fairly constant over time because they are defined by something that doesn’t change rapidly. And that enables us us to think about the price of things in much more fixed terms. The utility of this will become obvious over the next several posts, but, for now, just know that when I am referring to the value of something in terms of Wealth Units, I will call it the “wealth price.”

Analyzing the change in the wealth price of something yields great insight into what’s happening in the market. For example, what if the wealth price of cook pots goes down over time? It means that there has been a decrease in the total amount of materials costs and/or labor required to produce one. (This assumes quality and profit stay about the same.) For example, maybe the wealth price of metal has gone down because a new innovation allows it to be procured more efficiently. That will translate into a lower cost of producing cook pots and, thus, a lower wealth price.

Did you know that, when we quantify the price of something in terms of money–which I will call the money price–instead of Wealth Units, an additional confounding element is added? It’s true. Let me explain.

Let’s say that in Avaria they have been using gold pieces as money. They’ve been doing that for generations, and it’s been working out really well for them. But then suddenly the prominent local religion determines that worshiping calf statues made of bronze instead of gold is the proper way to honor the gods. The demand for gold has suddenly gone down, which means the value of gold has gone down as well. So maybe a single standard-sized gold piece used to be worth 1 WU, but now it’s only worth about 0.78 WUs. Therefore, the money price of that blacksmith’s cook pot has changed! He had a price tag on it that said “7 gold pieces”, but he crossed out the 7 and wrote a 9 instead. The customers might all complain, saying he’s gouging them! But really what’s going on is that the exchange rate from WUs to gold pieces has changed. The wealth price of the cook pot is still 7 WUs, but now he needs to get paid 9 gold pieces to recoup the wealth he invested in making it (because 9 gold pieces x 0.78 WUs/gold piece = 7.0 WUs).

People don’t understand this because, sadly, the wealth price is never written on price tags. Only the money price is written. So, when a money price changes, you can never tell if it is the result of a change in the wealth price or, as is the case from the above example, if it’s the result of the WU:money exchange rate changing.

In short, the additional confounding element included in every money price is the WU:money exchange rate. When that exchange rate changes, the money price changes along with it.

If this seems very theoretical to the point of not having real-world applications, go ahead and consider how the prices of things on the value menu of a fast food restaurant have changed from 2020 to 2025. Did the wealth price of buns and pickles and beef and teenage laborers change? Sure, during the COVID-19 pandemic, those things did temporarily change because of supply chain issues, decreasing supply and increasing prices. But even after supply chains went back to normal, prices remained much higher. It’s not because fast food restaurants are “price gouging” us and just getting away with higher prices because they think we got used to them. Nope, competition in the fast food market would dispel any of those attempts fairly quickly. The prices are higher because the WU:money exchange rate changed quite a lot. We call that inflation, and I’ll get to discussing exactly what that is (and exactly what causes it) later on. Part 3 here.

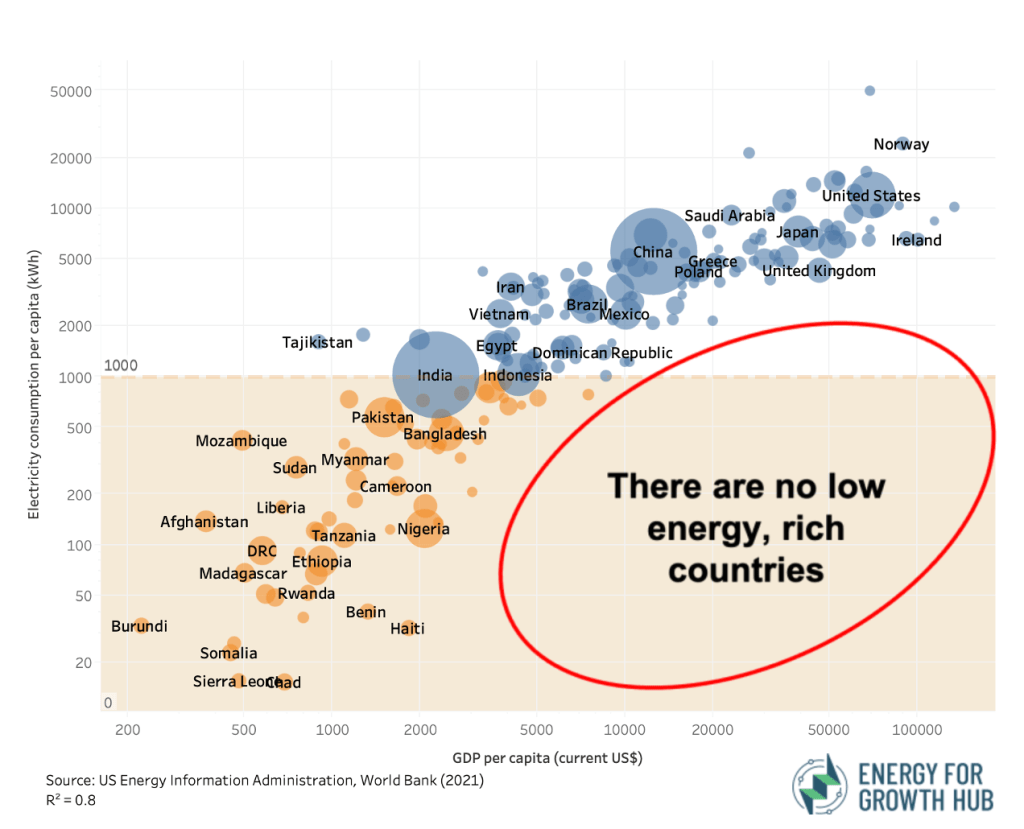

Addition 6/9/25: There’s a lot of talk about the connection between economic output and energy consumption, and I think this is a good place to explain that. When a worker is laboring, they are essentially taking their physical and cognitive energy and converting it to wealth. This could be through wealth gleaning, such as by picking fruit, or it could be by doing other things that are valuable to members of society, which leads to the worker receiving some already-gleaned wealth in exchange for that labor. Either way, the amount of wealth that can be generated by a worker is pretty limited when they are limited to just using their innate physical and cognitive effort. But when machines are invented to help with that labor, now we have access to other forms of energy inputs to generate wealth. For example, let’s say a loom is invented. This still relies exclusively on human inputs, but it at least makes that human input more effective, thus allowing the human to generate more than one Wealth Unit per hour. Now what if we made that loom solar powered? It’s taking an additional form of energy and contributing that energy to generating wealth. Looking at this from an aggregate perspective, when we can harness all sorts of non-human forms of energy (animal labor, solar, wind, hydro, fossil fuels, nuclear, etc.), we can generate a lot more wealth per hour of human effort. Therefore, an economy will be able to generate a ton of wealth per person (measured as the economy’s GDP per capita) if it’s consuming more non-human energy. And this is why the charts that compare countries’ energy utilization per capita with GDP per capita show such a strong positive correlation. The upshot of all this is that we need to have enough cheap energy to power all the machines we want to use. And having ready access to reliable and cheap energy will make businesses be much more willing to invest in machines to facilitate generating more goods and services.