After thinking and writing about healthcare for so long, I don’t often learn new things that turn out to be a big part of the puzzle. But this is one of them. I hope you can follow my thought flow as I explain.

First, I was thinking about something I’ve directly experienced a number of times. In talking to the upper-level managers of healthcare providers about their pricing, increasingly often they’re creating a list of cash-pay prices, which they use to determine how much to charge patients who either don’t have insurance or who, for whatever other reason, want to pay out of pocket for a service. But they’re almost never willing to have those price lists shared publicly.

Why?

Quick sidenote: The fact that providers are doing this so much more, and as pushed by some of the government transparency initiatives as well, is huge! Before, providers would use the chargemaster price when a patient wanted to self-pay. And since chargemaster prices aren’t even close to grounded in reality (for reasons that I’ve discussed before and won’t rehash here), it was a major ripoff if you didn’t purchase through insurance.

Anyway, the answer is that they worry that it will get them in trouble with insurers, presumably because if a cash price turns out to be less than the negotiated price with even one insurer, if the insurer finds out about it, the insurer will refuse to pay their previous (higher) price, so the provider will lose bigtime during the next round of contractual price updates.

Essentially, this means that providers’ attempts to create self-pay price lists (in an attempt not to screw over uninsured patients) could cost them a lot of revenue from insurers. So they keep them mostly secret.

And I suspect this is such an issue because of gag clauses in provider-insurer contracts. Gag clauses prevent either party from divulging the agreed-upon prices, which probably also indirectly prevent providers from being willing to share any prices publicly.

So that’s where my mind was at, thinking about this whole issue of price opacity and the fact that prices between private parties in healthcare are set through bargaining power-based negotiations between insurers and providers. And it led me to start thinking harder about the upsides and downsides of negotiated pricing versus standard pricing. Here is the definition I’m using for each of those terms:

Negotiated pricing is setting prices based on the relative bargaining power between the buyer and the seller.

Standard pricing is a seller setting their price wherever they want, and the buyer has a choice to buy from that seller or not.

The big realization I’m making–which also has big implications on why our healthcare system performs the way it does (as I’ll describe at the end of this post)–is that negotiated pricing kills a ton of value-sensitive decisions. Even worse, opaque negotiated pricing kills even more value-sensitive decisions.

The effect of something preventing a large chunk of value-sensitive decisions is that it weakens the link in that market between (1) delivering high-value products and services and (2) earning more profit. So the value delivered by that market no longer rises over time like it otherwise would because competitors are too busy competing over the new things (rather than value) that determine how much profit they will win. New things like market share, which empowers them to negotiate up prices. And we wonder why the healthcare market has rolled up (i.e., become consolidated into a small number of very large companies) like it has. How else can you earn more profits when prices are set mostly based on bargaining power-based negotiations?

Another side note: For those interested in business strategy, I’ve never heard anyone talk about this as a factor that pushes an industry to consolidate, but it’s probably a major factor in many industry roll-ups. Another factor, more well know, is if there are significant economies of scale to be had, that will also push an industry to consolidate.

So how does negotiated pricing kill value-sensitive decisions?

I’ve tried several times to explain this part, and I’m still failing to some degree, which means I haven’t pieced everything together well enough yet. So here’s my best shot, which might still be confusing.

When all the prices between insurers and providers are set through negotiated pricing, they aren’t as closely connected to what is truly valued in the market. This relates to the importance of prices in a free market and how they are the most important thing that conveys the value of something. Hayek wrote about this. So the prices don’t connect to what the true market price would be, which makes for an inefficient market when people are trying to determine and choose the highest-value options. There would still be a link between value and profit, it would just be a lot weaker. But, make it even worse by adding in the propensity for negotiated prices to be opaque, and now you’ve taken away the ability for individuals to know relative prices at all (assuming the prices are opaque to the decision maker), so you’ve completely killed value-sensitive decisions.

Related:

What I’m saying is that negotiated prices have caused two problems in our healthcare system: (1) The person making the decision on where they will receive care (i.e., the patient) no longer has any idea of the price of things, and they usually don’t care anyway because they usually pay the same amount regardless (through a flat co-pay, for example). (2) Sellers are unwilling to make any other prices public–including self-pay prices–for fear of it interfering with their gag clause or costing them money in the future when others demand that same price if it ends up being lower than a negotiated price.

The overall effect of shifting our healthcare system from its original standard pricing to negotiated pricing is that it eliminated a ton of value-sensitive decisions. And, once you hit a critical mass of non-value-sensitive decisions, the sometimes harsh incentive of the market for competitors to improve value (or else go out of business) gets significantly weaker.

So how did we come to have negotiated pricing in our healthcare system?

We had some amount of it even from the 1930s with Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, although the details of these arrangements suggest that they didn’t get translated into taking away the ability of patients to identify the price of their different options and choose accordingly.

But what really caused the shift was the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973.

Here’s some context for that Act: Healthcare innovation was increasing how much providers could do for patients, and some of those new things were very expensive. Consequently, the price of insurance was rising fast enough that people were trying to come up with new ways to lower healthcare spending. The big idea that took hold was to try to reduce the number of unnecessary services provided by providers by having insurers review proposed services and approve or deny them. It makes sense–fee-for-service providers get paid more when they do more, so they have an incentive to do more things for patients, including things that could be of dubious value. The solution worked, to an extent–the insurance companies were able to prevent a lot of questionable-value services from being performed.

This caused problems, too. The usual big complaints about HMOs is that (1) they would inappropriately deny things and delay services and (2) they caused a ton more administrative costs. All this is true. But possibly the biggest drawback is that it started us down this road of shifting to negotiated pricing.

When insurance companies starting forming HMO plans, they needed to have a limited provider network so that they could restrict their beneficiaries from receiving care outside of an HMO contract. Limited provider networks based on contracts between the insurer and the providers opened up another possibility for insurers: If a big insurer has a lot of market power by virtue of insuring a large percentage of the people in the region, they could start requiring providers to accept lower payments from them as a condition of being included in the HMO network. The providers were often willing to agree to that because of the additional volume it would bring them. But the insurer would also require the provider not to tell anyone else how much less they were getting paid by that insurer (a gag clause), which helped the insurer in a lot of ways, such as by preventing its competitors from finding out just how little they were paying, thus preventing competitor insurance companies from shifting their negotiation anchor regarding what kind of prices they could expect to have to pay.

So, overall, what I’m saying here is that an unanticipated side effect of HMOs is that they led to our healthcare system shifting from standard pricing to negotiated pricing, which eliminated a large chunk of the value-sensitive decisions in the market. And negotiated pricing through limited-network insurer-provider contracts remains even after the most aggressive versions of HMOs have gone away.

Now, what’s the big implication from this that I referenced above?

What would you expect to see if an entire industry of a country loses a ton of value-sensitive decisions in a relatively short period of time? Especially if this happens through a big shift toward opaque prices for the people who are choosing between different competitors, prices would no longer be constrained by the market, so they will start rising rapidly. There would also be an impact on quality–it would stop rising as fast as it was rising before.

If you wanted to take a more formal analytical approach to this, you could use a difference-in-differences approach by looking at how that country’s results change over time (before and after the change that reduced value-sensitive decisions) and compare that to how other countries’ results change over that same time period. Specifically, you would want to use as comparators countries whose markets didn’t go through that same change.

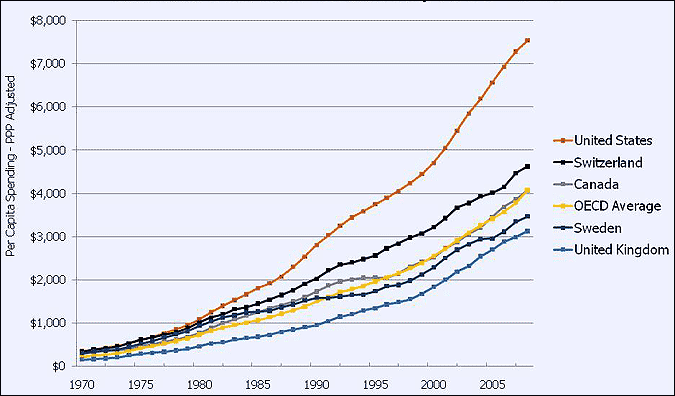

I’m not going to do a formal analysis like that right now. But, as you take a look at this graph, keep in mind that even though the HMO law was signed in 1973, HMOs didn’t really gain a ton of uptake until the 1980s:

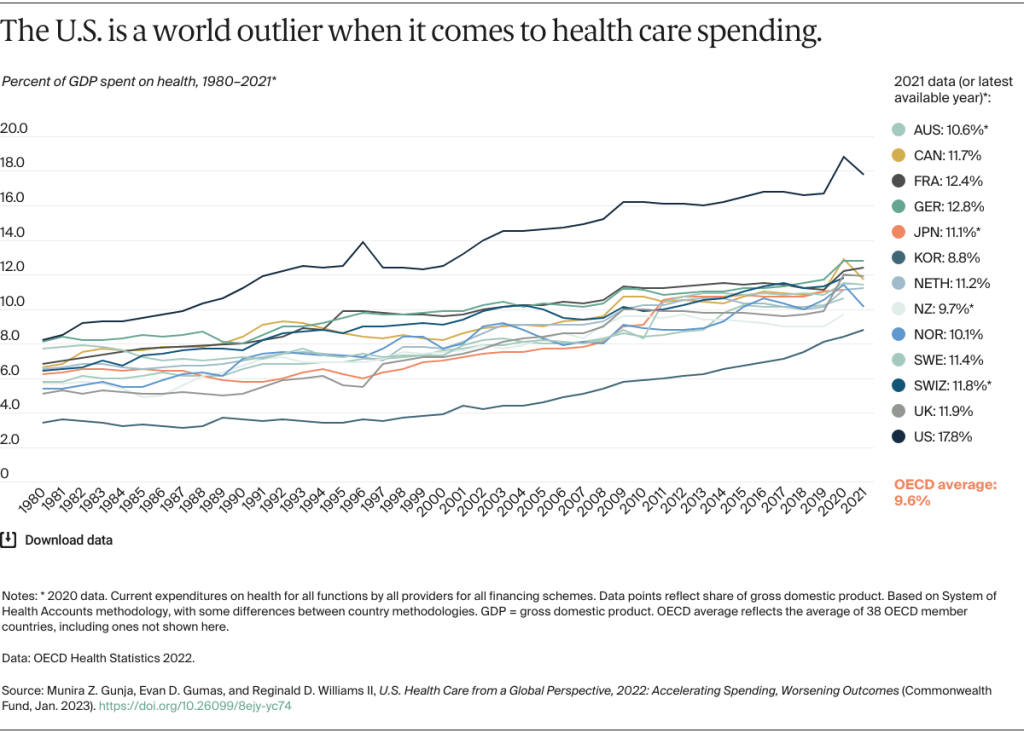

Here’s another one showing the same thing but with more countries. It just doesn’t go back as far in time:

I couldn’t find a longer-term graph to show, but I’ve seen them many times that show that the U.S. was middle of the pack for decades before 1980, and then something changed in the 1980s, and I could never figure out why.

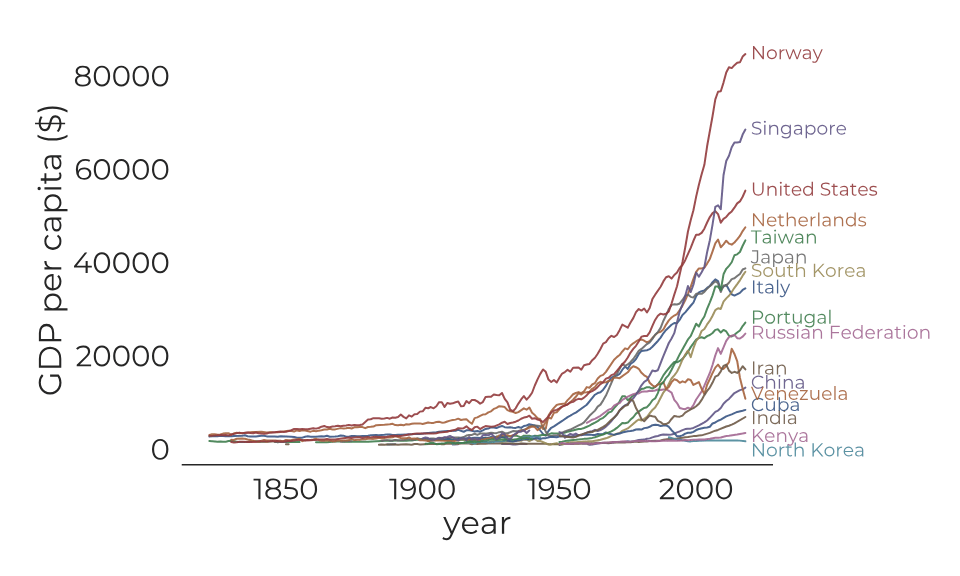

And for those of you who think that it’s because the U.S. started becoming way more wealthy than others around that time, take a look at this:

It looks like our rise in GDP per capita probably has some impact on why our spending increased as much as it has, but we don’t see Norway and the others becoming outliers like we have, so that implies the GDP issue is not the main factor here.

And on the topic of quality, it’s harder to compare country to country, especially when we don’t have universal coverage, so I won’t try to get into that in detail. Even looking at life expectancy is unreliable because a country’s healthcare system has such a small impact on that compared to the country’s culture surrounding diet and exercise.

So, that’s where I’ll leave it. I know there’s some uncertainty in this, but I am fairly confident that I finally have the answer to why the U.S. diverged in its healthcare spending in the 1980s–because we shifted from standard pricing to negotiated pricing as a result of HMOs.

And I have new evidence that is very consistent with my theory about how value-sensitive decisions are central to determining how much the value of goods and services provided by a market increase over time.

Update: I haven’t yet looked into how much the Price Transparency Act is likely to help with all of this. I’ll have to weigh in after I’ve analyzed it more thoroughly.