This is it! The final post of this series.

In Part 42, I described the “catastrophic method” for getting us back to a sound monetary system. In this post, let’s explore the gradual method for doing so.

First, to recap, what is the most sound monetary system we want to get to? A mix of commodity money and 100% backed receipt money. And to add a couple more specifics, we want the commodity that this monetary system is based upon to meet as many criteria as possible for optimal money, as described in Part 9, especially the “stable value” characteristic because accurate prices are the most important component to the health of an economy. The receipt money could be paper issued by banks or, potentially even better, electronically issued tokens by a few competing cryptocurrencies, but we probably don’t want people to completely switch over to using exclusively receipt money, so hopefully the commodity is convenient enough and beautiful enough and hard enough to counterfeit to be desirable for regular use as well.

So how do we go about gradually shifting to that kind of monetary system? There are three main tasks we need to complete:

- Get rid of the central bank

- Get rid of fractional reserve banking

- Trade out the 0% backed fiat dollars for an actual commodity

The first issue is a simple one. Repeal the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Calls to “end the Fed” would be satisfied with that simple repeal because it would immediately get rid of the Federal Reserve.

But what about the 20% of the total U.S. federal government’s debt that the Federal Reserve owns? I say repudiate it. This means those private banks that own the Federal Reserve will stop getting interest on all that money that they created out of nothing, but I think that’s ok because it’s time for the government to stop transferring our wealth to those banks. Remember how the only reason the government designed it this way was so it could get away with creating the central bank in the first place? There was otherwise no need for the government to be paying interest to anyone for creating more of its own fiat money.

Boom, 20% of the debt is gone. The other 80% will still need to be paid off through future taxation, but that can happen regardless of the monetary system we have. We’ll just have to keep waiting for the political will to do it . . .

Once we’ve gotten rid of the central bank, it means we still have a 0% backed fiat currency, but it no longer has the capacity to create any more money. This, in and of itself, would be a major boon to all Americans because now the government doesn’t have the ability to generate inflation, including unmeasured inflation (discussed in Part 35), which means the purchasing power of the money we’re earning would finally start consistently going up again after generations of stagnation. Without a central bank, another thing that would go away would be all the tampering with the money supply, which is done primarily through altering the required reserve ratio and the discount rate. We would have a stable money supply! The boom-bust cycle would be over. Yes, of course there would still be economic challenges, but at least the worst ones, which are induced by expanding and contracting our money supply, would be gone.

But we can do better than that–having a stable money supply is good, but it’s not nearly as good as having a stable value currency, which can only come through using a commodity to back our money. This is why abolishing the Federal Reserve is only the first of three tasks we need to complete.

Our second task is to eliminate fractional reserve banking. Why would we want to do that?

Because we want to stop banks from making exploitative loans using our wealth. We want that wealth back so that we can use it for ourselves rather than letting banks permanently borrow it and earn money on it.

Unfortunately, getting rid of fractional reserve banking is going to mess with our newly stable money supply. I’ve said before, though, that inflation or deflation isn’t so bad if it’s slow and consistent. So what we need to do is slowly raise the required reserve ratio until it’s back up to 1.0. For the sake of deflation being more predictable, I think the government needs to set the reserve ratio increase schedule, report it publicly, and then stick to it exactly.

How fast should we go? I suggest doing it over 30 years. This allows prices to adjust nice and slowly and also allows longer bank loans, such as mortgages, to mature naturally. And whenever a loan term is completed, the bank will probably not make a new loan. In this way, the reserve ratio slowly rises back up to 1.0. This 30-year timeline prolongs banks making exploitative loans with our wealth, but the benefits of stability to the economy probably outweigh that.

One thing to bear in mind while all of this deflation is happening is that the U.S. government still has 80% of its debt to worry about, and being a debtor during inflation is a bad position.

How does deflation harm debtors? If the WU:money exchange rate was 0.05 when the government borrowed $1 billion, that means it borrowed 50 million WUs. Then, if a lot of deflation happens so the WU:money exchange rate increases to 0.25 and the government hasn’t paid off its debt yet, the government now owes 250 million WUs. That’s not a good deal.

Rather than expect the federal government to pay off the rest of its debt before we start raising the reserve ratio, I say we simply have the government alter all of its debt contracts to say that the value of the principal will adjust with inflation or deflation.

There’s a little snag to this. Remember that economic growth increases the WU:money exchange rate. So if, during the time that we are phasing out fractional reserve banking, there is any economic growth, that means money will become more valuable, and this is an additional independent factor that will be increasing the WU:money exchange rate, totally separate from the shrinking supply effect on it.

So even if the government debt of $30 trillion shrinks with deflation over 30 years to be $3 trillion, the government will still be overpaying.

So maybe you add an adjustment factor for economic growth in there or something. Voila, math problem solved. Let’s move on.

So where are we now? The currency has become a 0% backed non-fractional reserve stable supply currency. Did you process all that? The point is, no central bank, and now no more exploitative loans, which means no more banks taking our wealth to earn interest off of it! Instead, we now get to keep our wealth.

This has been another huge step forward. But there’s one last task to complete: We need to shift our currency to a 100% backed currency.

The time has finally come to open Fort Knox–plus the other government gold repositories–and find out how much of the gold is actually left. Actually, we should audit the government gold stores at the very beginning of this whole process so that the government is unable to sell off any more of it without accountability. Yes, when everyone finds out that not all of the gold is there, it will threaten our status as the reserve currency for other currencies. But hopefully these efforts to get to a more sound currency will counteract that.

Once we have calculated the total amount of government gold stores, we do a simple calculation:

Total grams of gold / Total # of USD

And now we know how much gold each USD represents based on the existing stores. So, if we wanted to be hasty and immediately require everyone to switch out all of our USD for gold, there could be a redemption period where any owner of USD could bring it to Fort Knox and get the corresponding weight in gold. So if each USD ends up being worth 0.1 g of gold, that means you could bring $10 to the government vault and exchange it for 1 g of gold.

And this is where things get dicey. Because people are about to get hit with a loss of Wealth Units when they make that exchange. For example, if there’s only enough gold to give people 1 g for $10, but the market price of gold says that 1 g of gold is worth $20, people are about to lose half of their cash wealth when they are forced to make that exchange.

And the poor will get hit the hardest since they tend to have a larger percentage of their wealth stored in cash rather than non-cash assets. Some of that financial damage may be mitigated by the fact that, by this point, we will have been free from a 0% backed fiat currency for long enough that the wealth of Americans will be in a much better place, so instantly losing some percentage of their cash wealth would not be as devastating as it would be right now. But it would probably be devastating to many people nonetheless.

This “gradual method” has been trying to switch to a sound currency carefully to avoid sudden shifts in the value of money, so is there a way to do so in this third task as well?

Yes–again, we’re going to have to do it the slow way. Before retiring the USD and requiring everyone to exchange their Federal Reserve Notes for gold, the government will have to accumulate enough gold to be able to make the exchange at market prices to avoid causing anyone to lose any Wealth Units in the process. This would probably involve a requirement that the government use a certain percentage of its tax revenue each year to acquire gold. And that definitely going to increase the demand for gold worldwide, so it may be a rising target.

But, once the government finally has enough gold, it can lock in that market price as the exchange rate and initiate the exchange window of time. And when that exchange window ends, the government will officially declare the USD to be retired, and any remaining Federal Reserve Notes and token coins will be worthless from a currency standpoint.

*Moment of silence for the end of the USD* no, nevermind

One risk that is worth pointing out with this gold-accumulating method is that if the government declares that it is going to retire the USD and completely switch to gold, and then it announces how much gold it still has, the value of the USD may immediately drop to reflect the market price of gold.

Does this mean the government has to keep the amount of gold it has a secret? Maybe it does. But once the USD has been retired, then it can declassify how much gold there actually was. I hope they also release who spent the gold and how it was spent.

And there you have it. Task three complete: The currency has made its final transition to a 100% backed commodity currency. And now, finally, we can expect the value of money to be highly stable. There is sure to be some short-term price fluctuations with the final exchange of gold and USD, and there will be some mental effort of switching over to denominating cash wealth in terms of weight of gold. But just like you start to get used to prices pretty quickly when you visit a new country and use their currency, I think it will be a quick transition in the United States as well.

And then the competition will be on to see which form of 100% gold-backed receipt money–bank notes or crypto–wins out. Or maybe there will be room for all of them in the market. Ultimately, those details don’t matter nearly as much.

Now that we’ve discussed the catastrophic method and the gradual method for switching back to a sound monetary system, which one would you prefer? Which one do you think is most realistic?

I think the catastrophic method is more likely. It’s hard to imagine this ever happening since nearly everyone alive has only seen USD as the currency in America, but the history of the world is littered with the great empires of the past and their fallen currencies. My hope is that having the USD collapse as a currency will actually preserve the United States, so maybe the catastrophic method is better because it will get us to a healthier place faster. Rip the bandage off, right?

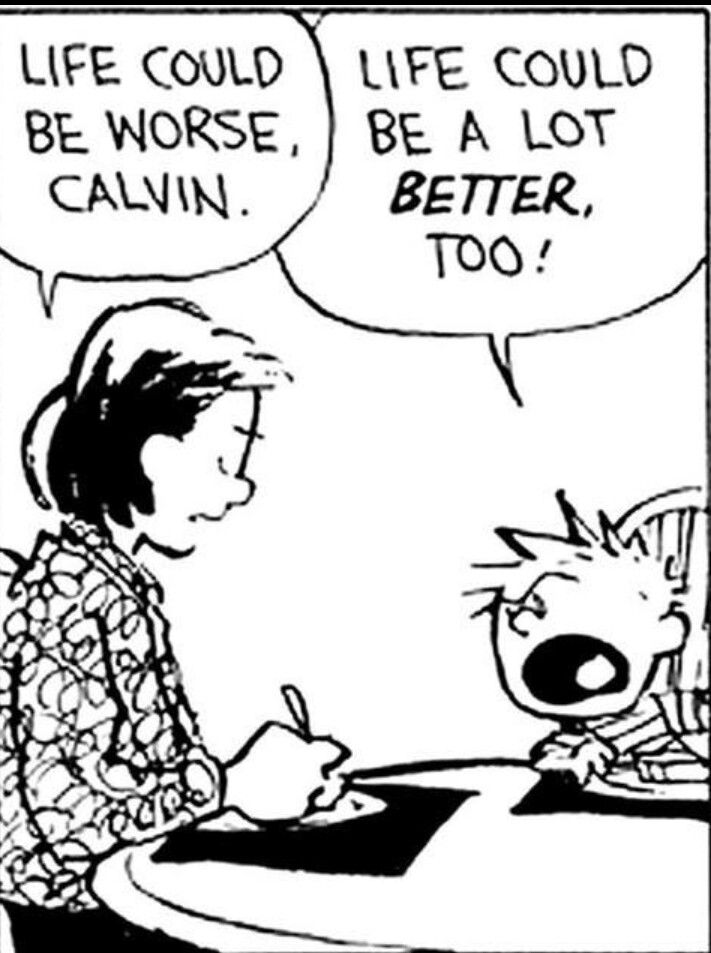

Understanding all of this creates a kind of strange persistent cognitive dissonance. On the one hand, my brain tells me that the USD will live forever, and my brain projects forward a future that is generally the same as the past but with more technology. And on the other hand, my brain knows that a correct understanding of the principles of how the world works–in this case, monetary policy–confers a powerful predictive ability, and I see the writing on the wall when it comes to U.S. government spending and the risk for eventual hyperinflation of the USD.

I see the Establishment, which I define as the millions of people who have found a way to take advantage of the complexity and non-transparency of our government and get a slice of the government spending pie, as the major driver of our government’s overspending. And, fortunately, the Establishment is not a monolithic unified group; rather, it’s people and their organizations that have found themselves in a position to profit off of the out-of-control government spending. And the fact that they’re not unified is a good thing, because it means they will all independently fight with every tool in their arsenal to influence politicians and bureaucrats to keep the money flowing to them. This is why any cut in government spending is so difficult. And it’s what will push us toward hyperinflation.

Do you see the irony here? The collective greed of the Establishment will become the means of our liberation from the bondage of our 0% backed fiat currency. But this won’t come without great cost to the generation that experiences it.

**********************

I guess that’s it. That’s the end of what I set out to explain about the theory of money.

I am struck right now by two things: (1) the extent to which we have been royally screwed by governments and their modern monetary policies, and (2) the extent to which people don’t even know that they’re being screwed. Heck, I had no idea about any of this, even after an undergraduate business degree from a traditionally conservative university, until monetary theory became a passion of mine and I started intensively studying the topic for fun. It’s been an incredible amount of reading and time and mind-twisting agonizing grappling with confusing ideas. And I hope the eventual clarity I was able to wrest from all of that miasma of confusion and complexity has been effectively conveyed in this series.

If, by now, you understand clearly that our 0% backed fiat currencies are a form of wealth bondage that has stolen the prosperity that our parents and grandparents labored so hard for us to get, then you might be angry. Maybe you’re even looking for someone to blame.

The problem is, we can’t really blame anyone for this. The two groups most responsible for getting us here–politicians and bankers–have made rational and even justifiable decisions all along the way, which I’ve tried to show in this series. I guess the default path of some things in this universe tends toward bad outcomes. And the economics of money is one of them.

So instead of reacting unproductively to that anger, I hope you can channel it into motivation to help fix things. Talk to people about these ideas. Share them. Support politicians who are pushing for the necessary changes. The more these ideas spread, the more support for the right kind of policies will arise, and the more likely we are to win in this fight for freedom from monetary system bondage. And maybe, in the future when new governments and monetary systems are being crafted, the right constitutional restrictions will be put in place to prevent these issues altogether.

Thank you to everyone who has followed along for almost a year of money blogging (on a healthcare policy blog no less!) as I sated my desire to make this information accessible to the world. I hope it has enriched your life and made your dreams of a better world more vivid.