In Part 27, Avaria finally transitioned to a centralized currency. To be clear, its money is still 20% backed by gold (based on a reserve ratio of 0.2), but its receipt money is now uniformly First Bank Notes. And now the only way someone can get an actual gold coin is by going to a First Bank branch and trading a First Bank Note for one, which I mentioned people are doing less and less as the years pass and they get used to exclusively transacting using First Bank Notes.

For clarity in my terminology, I will now only use the term Goldnote to refer to the pre-centralized currency. And I will only use the term First Bank Note to refer to the post-centralized currency.

One other terminology clarification: To refer to the non-government-run banks, I’ve been calling them “private banks.” But, realistically, if they are owned publicly (with bank stock freely available to purchase on the stock market), then the term private bank is probably no longer appropriate. So, I will call them “commercial banks” instead.

All right, with those terminology clarifications aside, let’s see what happens next.

Since the transition to a centralized currency, transacting has become easier because now everyone is using the same notes instead of a bunch of different banks’ Goldnotes each with its slight difference in valuation (according to the reputation/riskiness of the issuing bank).

Importantly, gold (and some other non-cash assets maybe) is still the only form of reserves. That will eventually change, but for now reserves are still only intrinsically valuable assets.

So, now that the commercial banks are no longer able to issue their own currency, what do they do?

As we discussed with Astro Bank in Part 27, not much has changed. It still has its reserves (which are now “reserve credits” at First Bank rather than piles of gold coins in its own vault), and its sole revenue stream continues to be lending out money in accordance with how many reserve credits it has. But commercial banks no longer deal in gold coins. If a depositor comes to Astro Bank hoping to deposit a gold coin, Astro Bank refers it over to First Bank, where the customer will receive 1 First Bank Note in exchange for each gold coin they deposit. And then the customer could turn around and bring those First Bank Notes to Astro Bank to deposit them for safe keeping.

Annoyingly for the commercial banks, even if they do a great job enticing many new customers to deposit their First Bank Notes in their vaults, none of that will increase their reserve credits. So their income from a lending perspective is capped at what it was when the transition to a centralized currency took place.

They can still find other ways to earn money, such as by helping customers invest the money stored in their vaults and charging advisor fees, or by utilizing all that newly emptied space in their vaults to store other forms of valuables for customers. So there is some amount of competition between the banks to win customers so they can provide those extra services to them. As part of that competition, the banks want to make transacting with their bank more convenient, so they eventually invent checking accounts, which allow depositors to basically just write an IOU when spending money at any merchant, and the merchant will take that IOU to the customer’s bank and have the money deducted from the customer’s account and given to the merchant.

But, overall, the private banks are unsatisfied because their primary source of income–loaning money–is capped, all while they are accumulating huge piles of First Bank Notes in their vaults that are “just sitting there doing nothing” (this is a reference to what our original banker said in Part 10, and which should give you a hint about where this is going . . .).

I’ll get to that in Part 29.

And, to finish out this part, let me clarify a couple more changes that occurred as a result of centralizing the currency.

I first want to describe how the specie pool changed. Remember how banks would lend reserves to each other through the “specie pool” if, at the end of a day, a bank’s reserve ratio was below the agreed-upon minimum and another bank had excess reserves?

Well, the same thing still happens, but the process is slightly different.

At the end of each day, each commercial bank reports to First Bank the total value of its outstanding loans. If that number is more than 5 times its reserve credits, it is short on reserves and needs to borrow some reserves from another bank. First Bank will facilitate an overnight transfer (purely an accounting process) of reserve credits to the bank that is short from any bank that has excess that night, and the borrowing bank will pay some interest to the lending bank. Commercial banks negotiate over the interest that will be paid, and that interest rate is called the interbank lending rate.

However, if no bank has enough excess reserves, then the commercial bank that was short on reserves will have to borrow some reserve credits directly from First Bank (the “lender of last resort”), which has the authority to (1) create out of thin air new reserve credits for lending and (2) unilaterally set the interest rate on borrowing those newly created reserve credits. First Bank will set that interest rate fairly high so that it will discourage too many banks from being overly aggressive in how much they are lending relative to their reserves. Plus, as a nice perk, this is yet another way for the government (through First Bank) to get some of the profits that this banking industry is making!

For reasons that aren’t relevant to this discussion, the historical term for the place where a commercial bank employee could go to the currency-issuing bank to borrow overnight reserves like this was called the “discount window,” and the interest the commercial bank would pay for those reserve credits was (and still is) called the “discount rate.”

Let’s discuss one more change that will happen as a result of all the gold being consolidated in First Bank’s vaults.

Imagine having a bunch of vaults that everyone knows are packed with all of the country’s specie in gold. Kind of a scary thought, right? First Bank vaults have become a major target for anyone in the world looking to get rich quick by stealing tons of gold that they can make untraceable by melting it down and re-casting it.

Sooner or later, First Bank is going to need to find a way to store this gold more securely. It eventually determines that storing the gold in just a few super secure locations will be safer and more efficient. So, we can eventually (say, within the 20-30 years after centralizing the currency) expect at least one giant vault to be built, and a large percentage of the total gold will gradually be moved there.

Fort Knox, anyone? The U.S. formalized its centralized currency via the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, which induced the transfer of all the gold in commercial banks’ vaults to the Federal Reserve bank vaults. And, 23 years later, in December 1936, Fort Knox was completed, and by the end of 1937 a huge percentage of the gold reserves had been moved there.

Is the gold still there in Fort Knox? I suspect it isn’t, for reasons that will become clear later on.

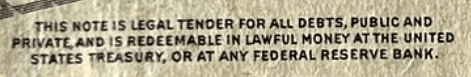

One last thing for this post: Another benefit that First Bank now has is the fact that, with a monopoly over printing First Bank Notes, invariably some percentage of them will get lost or ruined each year, so First Bank can print new ones to introduce into circulation and prevent deflation from a gradually diminishing money supply. Who should it give these new First Bank Notes to? There’s no way to know who actually owned the First Bank Notes that got lost or destroyed, so it will simply give them to the government to spend. President really likes this new source of free money!

Phew. That was a lot of information to process from that change to a centralized currency.

As an aside, what a fun journey to be on, right? Figuring out money and banking, and also figuring out how to explain it in a comprehensible format, is much more interesting than I ever expected. Maybe because I’ve come to appreciate just how important these things are to understanding why our modern economies are getting messed up in serious ways. If you haven’t ever read anything on money and banking, you should try it. For example, try reading these speeches (PDF) made by some Ph.D. economists during a United States congressional hearing on fractional reserve banking in 2012. If you already understand what they’re talking about, their statements make sense. But if you don’t, man is it all befuddling (which I suspect is partly on purpose to help preserve the whole banking industry’s wealth-stealing scheme by hiding it behind Byzantine institutions and terminology). I’m sure I fail sometimes at demystifying it, but I hope my deliberate stepwise approach to this information (plus some simplifications that don’t alter the underlying mechanics) helps.

All right, in Part 29 I’ll add some technology into the mix and then jump right to transitioning to the next phase in the evolution of money.