In Part 18, I explained the financial details of Independent Bank to show more thoroughly how the financial shock led to a drain on the bank’s reserves and triggered the bank run. Here’s a quick recap of that to clarify it:

- Avaria’s 5 banks are simplified banks with only one source of revenue: the interest they earn from lending out the money they created through fractional reserve banking

- These banks have fixed costs (building maintenance, wages, etc.), which need to be paid for with the interest income they are getting

- If a bunch of borrowers default at the same time, a bank’s revenue may drop below its costs, which would mean it is stuck trying to pay its costs either with even more newly created money or by paying directly with specie it has in the vault, both of which result in the same problem–even lower reserve ratios, which always translates into even more severely depleted stores of specie

- Depleted reserves trigger bank runs when word gets out and people get scared

Before I describe the ingenious solution the banking leaders come up with to prevent Avaria’s entire monetary system (the house of cards) from collapsing, how about I describe the likely outcome of this situation if the banking leaders did nothing? Yes, it’s time to see how damaging fractional reserve banking can be to a society when it leads to bank failures.

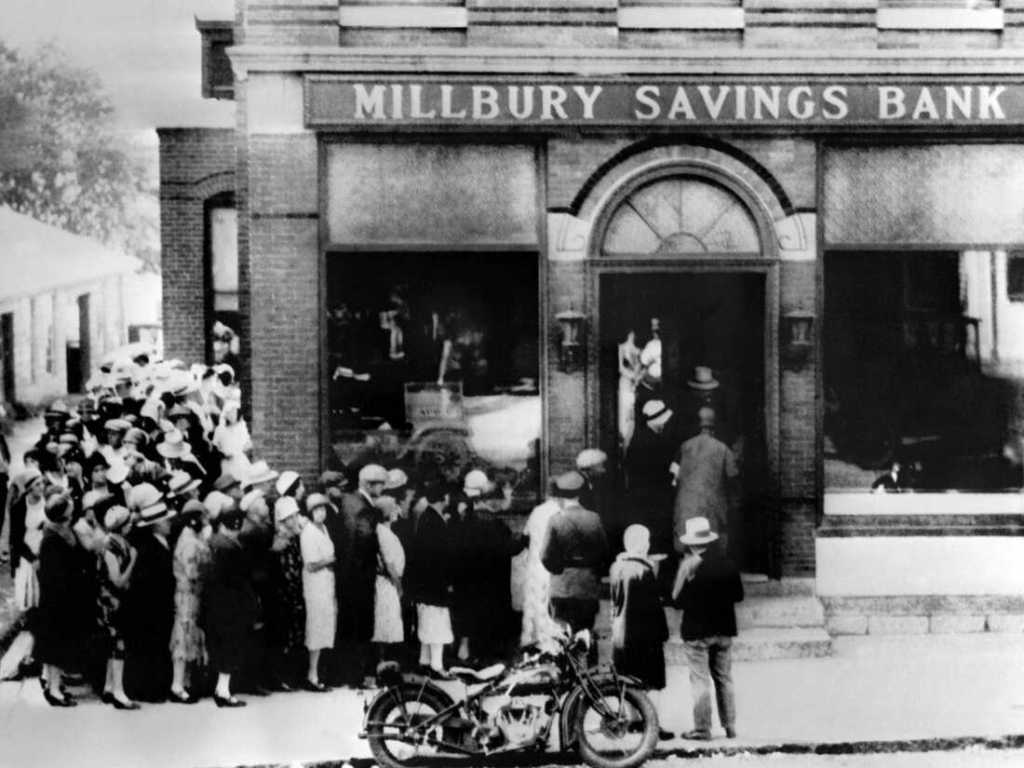

First, the people in line at Independent Bank see people from the front of the line walking away with bags of gold coins that they received in return for their Goldnotes. But then, finally it happens–someone gives the teller a pile of Goldnotes and requests they be exchanged for gold coins, and the teller comes back with only a few gold coins in hand, apologizing that these are the last of the gold coins from the vault, and the bank forces everyone out and closes its doors. The other customers who were in line freak out, realizing that their Independent Bank Goldnotes are now worthless. If only they’d gotten in line earlier, they could have avoided losing all that money!

What do they do? They immediately go home and collect all the Goldnotes that they own from the other four banks and send them with family members to the originating banks so they can get in line early enough to exchange them for gold coins. Soon, word spreads and long lines form at the other four banks. And, of course, since the other four banks don’t have enough gold coins in their vaults to redeem every Goldnote they have in circulation, they all close their doors as well.

Within a few hours, Avaria went from an illusion of prosperity to a financial panic. Some people lost all of their cash wealth because they didn’t get in line early enough, and now they’re worried about starving. Stores stop accepting those worthless Goldnotes and demand gold coins for payment. But prices are still so high from Avaria being flooded with money lately that few have the money to buy much, which furthers the economic upheaval. In the panic, mobs of scared people are entering grocery stores and looting whatever they can carry home.

Why are prices suddenly so “high”? Remember that the money price of a thing is determined by the WU:money ratio. Prior to fractional reserve banking, a gold coin or Goldnote was worth 5 WUs (see Part 12). But then, after the institution of fractional reserve banking, 33,000 Goldnotes were circulating, which diluted the same number of WUs over a much larger number, so each Goldnote came to only be worth 1.5 WUs. And with the recent banking competition pushing banks to decrease their fractional reserves further, it would have dropped lower than that even. For simplicity, let’s say that each Goldnote represented 1 WU when this panic started. So if the true price of all the food needed to feed a small family for a week was 20 WU, its money price listed at the grocery store would have been 20 gold coins (or, equivalently, 20 Goldnotes). But now that all the Goldnotes are deemed worthless and not accepted as a common medium of exchange anymore, the WU:gold coin ratio is back up to around 5:1. So if, on the day of this panic, someone actually paid the full listed money price with gold coins, they would be paying 5x too much! They should only pay 4 gold coins if the money price had adjusted instantaneously to account for the new WU:money ratio, but instead customers are being asked to pay 20 gold coins. And since money prices only gradually change as store owners slowly acquire information suggesting that money has come to be worth more again, those artificially elevated prices will stick around for a while. This is why people are panicking even when they have 40 gold coins–it seems like they only have enough money to feed their family for 2 weeks.

Even though money prices will gradually adjust to the new WU:gold coin ratio, the damage will already have been done. There was a horribly uneven redistribution of cash wealth because some people lost all of their cash assets and other people (who got in line at the banks early enough) found that they ended up with more cash assets than before. And others were stuck overpaying up to 5x for things they desperately needed. There was social upheaval. There was crime. There may have been starvation in spite of an adequate aggregate amount of food. Investment into new ventures screeched to a halt, and other new ventures failed. What I’m describing is the aftermath of a societal default.

In additional to all of that, the trust in banks as a whole was completely lost, which will probably last a generation or two until the societal memory of the event fades and new bankers find a way to brand themselves as wholly different than those “bad” banks of generations past.

Meanwhile, the Avarians still don’t clearly understand how it all happened–the banking system had become so obscure, perplexing, and incomprehensible. (Which is a myth! That’s why I’m writing this series!) So the Avarians will probably find themselves with fractional reserve banking again eventually, not knowing that a simple bank auditing system (as described in Part 13) could prevent all that damage from coming back and progressing to even worse damage as their monetary system once again travels down the natural evolutionary path of money.

Pretty bleak, right? It all seems so unbelievable to our modern sensibilities, doesn’t it? But here’s the thing–these very events (societal defaults, usually driven primarily by bank leverage and also government leverage, as we’ll see later on) have happened to many societies in the past, in the United States and elsewhere, and they happen in modern societies as well.

Unfortunately, societal memory fades so quickly that these things happen over and over again, often within even just a couple of generations. A little understanding of the history of money in the general populace can help prevent us from being “doomed to repeat” that history because people won’t support policies that they know will lead to these sorts of issues. That’s why I’m writing this series!

And now let’s get to what actually happened in Avaria.

The banking leaders decided to act as soon as they saw that long line of people at Independent Bank trying to exchange their Goldnotes for specie. Remember, the bankers know perfectly well that Independent Bank will run out of specie before the day is through, which will likely lead to lines at all of the banks and kill the goose that is laying the golden eggs for them.

First, they organize an emergency meeting. The leaders of all 5 banks are there, although the leader of Independent Bank is in the corner playing a morose song on a lute.

The other four leaders initially talk about allowing Independent Bank to declare bankruptcy and then spinning this to the public to convince them that Independent Bank was the only imprudent bank and that all the rest of them are very safe. Their hope would be that a strong and widespread PR campaign will prevent generalized distrust in the banking system (and the ensuing lines at their doors requesting specie) after Independent Bank goes bankrupt. They would then have to prove how safe they are by being a little more conservative (at least for a while) with their reserve ratios and loan risk.

But after discussing this idea for a while, they are not convinced it would work. Even with a great PR campaign, there is still a reasonable risk that the panic will spread to the other banks, and they know none of them would be able to weather that storm. And, they reason with themselves, they can’t let that happen for the sake of society–think of how disruptive to society it would be if the banks go away! For the sake of the people, they tell each other, it is their duty to find a better option.

So, they hatch an ingenious solution. The society’s original goldminer-turned-banker, the proprietor of Peppercorn Bank, has a thoughtful look on his face for a while and then says, “What if . . . hmmm. Hear me out on this one because I just had an idea that sounds a little crazy but might work. You see, us other four banks still have gold coins in our vaults, right? What if we lend Independent Bank some of those gold coins–just for the short term–to help it avoid bankruptcy? We could make a big show of delivering cartloads of gold to Independent Bank. The people in line will see all that gold, and they’ll see the people at the front of the line walk away one by one with all the gold coins they requested, and eventually they’ll start to second guess their decision to waste all that time waiting in line when it seems that there are enough gold coins for everyone. Eventually, their panic will subside enough that the line will dissolve. We can then think of a clever marketing campaign to explain how what happened was pure unfounded public hysteria and insinuate that it was selfishness on the part of the individuals who were at the front of the line requesting all those gold coins, and in that way we can reassure everyone that the banking system as a whole is rock solid.”

Eyebrows were raised, and then two concerns were also raised.

The first concern was that this could make one or more of the other four banks run out of specie. This concern was overcome easily by clarifying how much each bank could afford to lend and by realizing that the loan to Independent Bank would probably only need to be for a very short term, maybe even just for a day or two.

The second concern raised was more difficult to overcome. Someone pointed out that if they bail Independent Bank out like this, it will create bad incentives for all banks. It would essentially be taking away the consequence for too-risky lending and too-low reserve ratios, so all the banks would then have an incentive to engage in risky behaviour just like Independent Bank had been doing, knowing that they can get away with high risk and high rewards and, if anything goes wrong, they’ll simply be bailed out by the other banks. And, if that happens, there may not be enough reserves in the other banks to bail them out if everyone is behaving in such a risky way like this.

So they decided that there should be a price associated with needing to be bailed out. They would charge a high daily interest rate on any specie lent from another bank. This solution would actually turn out to be a win win because it alleviates the bad incentives while generously compensating the lending banks at the same time.

In the end, they collectively agreed to this solution and put it into writing. They then immediately sent word to the other four banks to start carting gold coins to Independent Bank. Within hours, their scheme had worked and the panic had dissolved. Crisis averted. Phew, that was really close to a societal default!

This solution was pretty tricky, right? The bankers just invented something new. If you’ve heard the term central bank before, you should be aware that I don’t like that term applied to this arrangement because it is misleading and confusing when real central banks are discussed (we’ll get there). So I will refer to this solution they came up with as a mutual specie reserve agreement, or a specie pool for short.

Where is Avaria’s monetary system now? It still has fractional reserve banking, and now it also has a specie pool to help the banking system be a little more stable so the bankers can continue to milk the cash cow that is fractional reserve banking.

In Part 20, we’ll look at how societal leverage contributed to this situation, and we’ll also talk about societal diversification as a means of reducing the risk of a societal default.